Politics and the Utopian Dream

Photography’s ability to abstract time and space provides a

potent vehicle with which to communicate a point of view.

Whether migrating a nation to a utopian social and economic order or framing public policy debates, the power

of the photographic image was used effectively in the 20th Century by both totalitarian and democratic leaders.

This exhibition illustrates its power to inform and influence. It reminds us of the future impact potential

of imagery to amplify ideas using an array of new electronic technologies.

Photography as Propaganda – Politics and The Utopian Dream

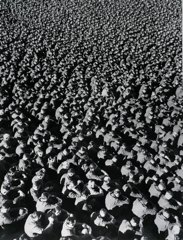

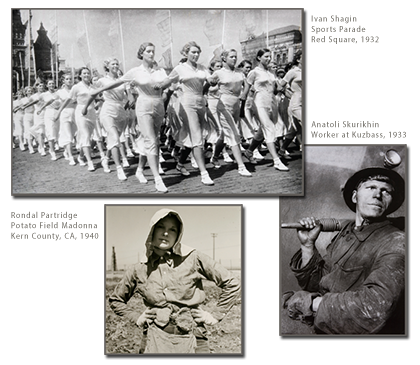

Photography, as with much of the art in the three decades following revolutions in Europe and WW I, reflected both creative expression and propaganda. Totalitarian and democratic leaders alike used images as a major tool in their “information” programs trying to move nations to a utopian economic and social order. The Roaring Twenties in the U.S. was fed by a robust investment engine, while Germany struggled to escape the burden of reparations debt and the Soviet Union tried to transform a serf-based agrarian economy. The United States government allocated significant resources to create a national self-portrait endorsing political policies. While the Soviet people endured hunger and slave labor to build an industrial base, photography was used to create the illusion of a modern state. And, in the Third Reich, the importance of the story line was always recognized by Hitler, “Propaganda is a truly terrible weapon in the hands of an expert.” — Mein Kampf, 1925

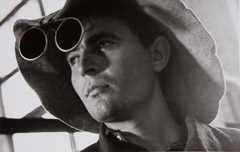

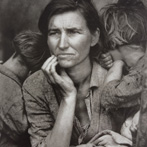

This exhibition starts by depicting the post war modernist view that technology could help construct a utopian social order. Deteriorating economies led to a growth in totalitarian governments, conflict of political visions and accelerated use of visual propaganda in photography and posters. The rear gallery demonstrates the scale and diversity of war images as government information bureaus worked to build morale and support through state sponsored propaganda. Reality was often held hostage to staging, technique and editorial license.

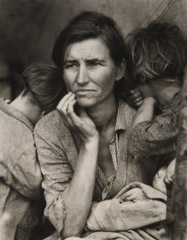

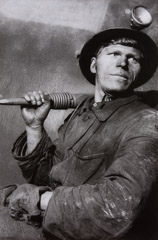

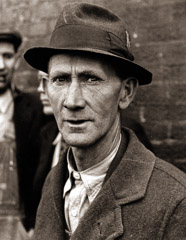

The front gallery illustrates not only the commonality of conditions in America and the Soviet Union, but also the diversity of message employed by each. In spite of deteriorating economic conditions and conflicts, life went on in most of the world. Ironically, Stalin’s regime was focused on constructing uplifting, optimistic images to create hope for Utopia and to mask widespread repression. The publication USSR In Construction exported that message in five languages. Roosevelt’s New Deal primarily commissioned work reflecting poverty and hardship. The gallery also shows heroic representations of workers and athletes. This technique was mainly seen in the USSR. Though some U. S. photographers did view an optimistic side in the American spirit, it was in counter-point to most photographers of the depression era. New, powerful image processing software… real time network media… on line periodicals and social networks now exist. The 21st Century’s accelerating availability of these tools for effective propaganda places a premium on self imposed filters and judgment as the political process expands imagery’s use toward its own ends.

We hope that this show will stimulate recognition of the dual potential of powerful images to inspire and, when negative, to exact a large toll.

Featured in this exhibition is the work of numerous photographers, 10 are highlighted below.

Select the image below to view the complete artist page for these photographers.

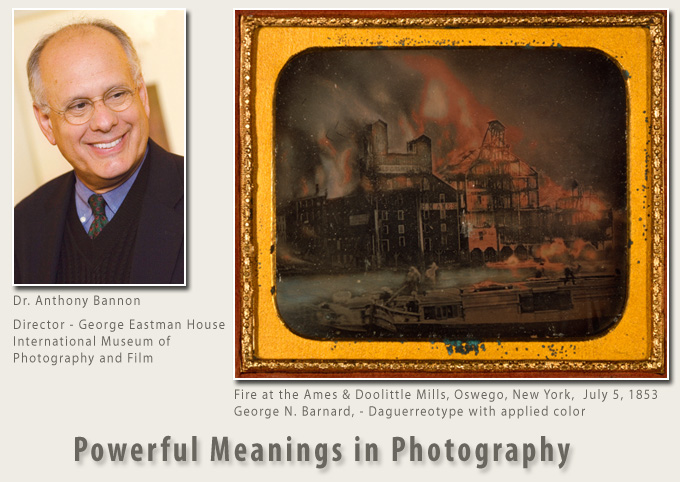

Powerful Meanings In Photography

Dr. Anthony Bannon, the Director of George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, discussed the use of photography throughout history to communicate powerful messages and create lasting cultural icons. The program, part of the Annual Lumiere Lecture Series, was offered in collaboration with the High Museum of Art and Atlanta Celebrates Photography.

The audio clip below is a small excerpt is from his closing remarks, as he discussed the nature of the single photographic image and speculated on future of the medium of photography.

Biographical Information:

Dr. Anthony Bannon was the Director of George Eastman House – International Museum of Photography and Film: the world’s oldest and largest independent museum dedicated to photography and film. He has held that position from 1996 to 2012. Prior to his time at Eastman House, he served as director of Burchfield-Penney Art Center, director of cultural affairs on the campus of State University of New York, College at Buffalo and as an editor and art critic with The Buffalo News. He has also worked as a filmmaker. In 2012 Bannon retired from George Eastman House and returned to his previous position as director of Burchfield-Penney Art Center in Buffalo NY.

Dr. Bannon has lectured at museums, colleges, and festivals worldwide. He currently serves as chairman of the Lucie Awards/International Photography Awards. In 2007, Bannon was awarded the Golden Career Award by the FOTOfusion Festival of Photography & Digital Imaging for his “far-reaching leadership and scholarship in the cultural community.”

Bannon’s 16-year tenure at George Eastman House resulted in major acquisitions, alliances with museums and universities, innovative conservation efforts, as well as the creation of three post-graduate preservation schools and collectors clubs in large American cities.

ArtCriticATL – Exhibition Review

Alluring and Illuminating “Photography as Propaganda” at Lumiere

October 11, 2011

By Robert Stalker

What countries could be more different than the Soviet Union and the United States during the first half of the 20th century? Yet, as suggested by Lumiere’s illuminating “Photography as Propaganda: Politics and the Utopian Dream,” many of their ideals and fantasies were actually alike, and so were the images that served their goals and cultural values.

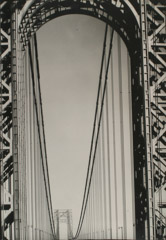

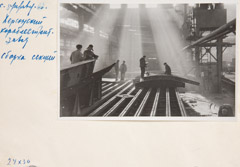

Inspired in part by “Propaganda and Dreams,” the 1999 exhibit at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, the exhibit opens with pictures by American and Soviet photographers celebrating technology and the built environment. Margaret Bourke-White’s “George Washington Bridge” (1933) and Berenice Abbott’s “Night View, New York” (1932) sit alongside contemporary photographs of the Dneprostroy Dam and Kherson Shipbuilding Factory by Max Alpert and Simon Fridland, respectively.

The photos were produced in divergent contexts with quite different aims. Bourke-White worked for the capitalist Henry Luce’s Fortune as well as Look magazines, creating photos that seemed almost to advertise the romance of commerce and industry. Abbott worked independently in the 1930s on her “Changing New York” series, promoting a view of urban planning that she continued under the sponsorship of the Federal Art Project. Fridland and Alpert documented Soviet manufacturing and engineering for government news platforms such as ITAR-Tass, Izvestia and Pravda, constructing the not entirely accurate impression that the young, impoverished nation was heading full steam into the 20th century. Despite these differences, however, the photos share an almost palpable optimism about technological modernity and its culture of speed and mechanization…… ArtsCriticATL. Follow this link to read the entire review. (opens new browser window).