Ansel Adams

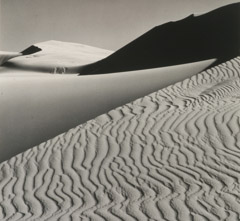

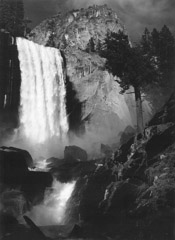

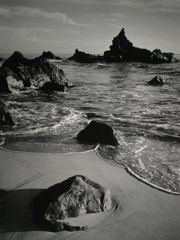

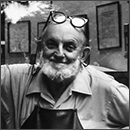

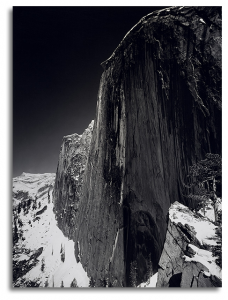

Ansel Adams (1902-1984) One of the greatest artists of modern time, Adams has had exhibitions of his images at most of the world’s major museums. Dozens of books have been published on his work. He is the recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Pirkle Jones served as his first technical assistant. Their association continued over four decades. Photographer, conservationist; born in San Francisco. A commercial photographer for 30 years, he made visionary photos of western landscapes that were inspired by a boyhood trip to Yosemite. He won three Guggenheim grants to photograph the national parks (1944-58). Founding the Group f/64 with Edward Weston in 1932, he developed zone exposure to get maximum tonal range from black-and-white film. He served on the Sierra Club Board (1934-1971).

Born: February 20, 1902 – Died: April 22, 1984

The work of Ansel Adams is featured in these exhibitions.

(Select the image to view the exhibition page)

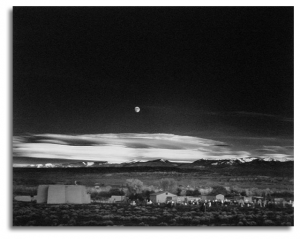

The Spiritual Impact of Ansel Adams’ Work

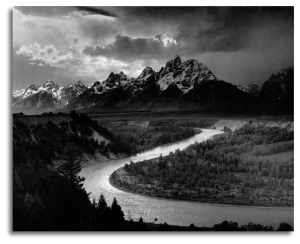

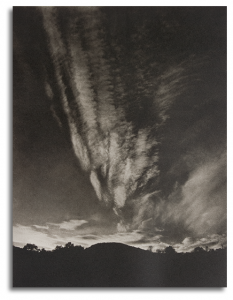

Looking at Ansel Adams’ pristine rendering of the natural world in all its unspoiled glory can be a spiritual experience. Standing in the scene, feeling the sting of the wind and the warmth of the sun, being immersed in a silence punctuated only by weather and animal song must have been truly special for Adams. His lifelong devotion to a deeper understanding of the wilderness, beyond physical beauty, proves its importance to the artist.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

ANSEL ADAMS & TODAY’S TECHNOLOGY (1 of 4)

ANSEL ADAMS – EARLY MODERNIST (2 of 4)

ANSEL ADAMS – EXTRACT OVER ABSTRACT (4 of 4)

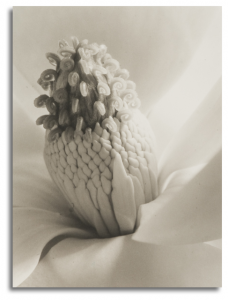

Ansel Adams - Early Modernist

Group f/64 – Pivotal Role in 20th Century Photography

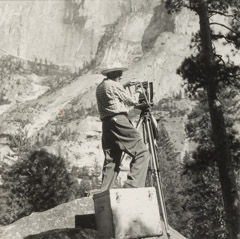

Modernism is a slippery word. When we hear this term, many of us think of sky scrappers or avant-guard furniture. The timeless beauty of a snowy Half Dome at Yosemite or or El Capitan as captured in the photographs of Ansel Adams may not be the first images that leap to mind, but increasingly scholars are considering Adams as an early modernist.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

ANSEL ADAMS & TODAY’S TECHNOLOGY (1 of 4)

THE SPIRITUAL IMPACT OF ANSEL ADAMS’ WORK (3 of 4)

ANSEL ADAMS – EXTRACT OVER ABSTRACT (4 of 4)

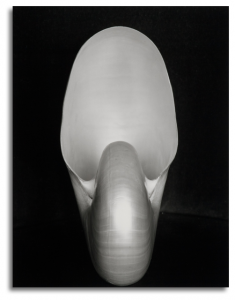

Ansel Adams - Extract Over Abstract

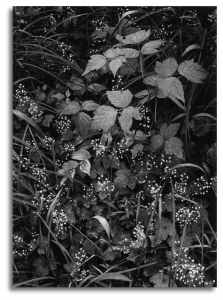

A Blend of Philosophy and Technique to Create Majestic Photographs

Meticulous. Premeditated. Studious. Considered. Designed. Projected. Predetermined. All synonyms for the word deliberate. Ansel Adams just might have been the most deliberate photographer to traverse the American West. Adams crafted his exacting approach to photography by employing both technical and philosophical processes.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

ANSEL ADAMS & TODAY’S TECHNOLOGY (1 of 4)

ANSEL ADAMS – EARLY MODERNIST (2 of 4)

THE SPIRITUAL IMPACT OF ANSEL ADAMS’ WORK (3 of 4)

NPR: Update on Search For Next "Ansel Adams"

January 27, 2016

The National Park Service is hiring a full-time photographer to document the country’s natural landscapes. NPR’s Audie Cornish talks to Rich O’Connor of the National Park Service photography program about the position, which some are comparing to the job held by Ansel Adams in the 1940s.

Ansel Adams & Today's Technology

Would He Embrace Photoshop?

Would Ansel Adams sit behind a computer in his Carmel home, editing his latest photograph in Photoshop? Would the man who wrote dozens of books, including volumes called: The Negative and The Print, archive his RAW files in Lightroom? Would the man who championed the zone system, now create apps and plug-ins? More than 30 years after this influential photographer’s death, younger generations of artists are asking similar questions.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

ANSEL ADAMS – EARLY MODERNIST (2 of 4)

THE SPIRITUAL IMPACT OF ANSEL ADAMS’ WORK (3 of 4)

ANSEL ADAMS – EXTRACT OVER ABSTRACT (4 of 4)

Ansel Adams' 113th Birthday

February 20, 2015

“I am sure the next step will be the electronic image, and I hope I shall live to see it. I trust that the creative eye will continue to function, whatever technological innovations may develop.” – Ansel Adams

One of the greatest artists of the 20th century, Adams was a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He made visionary photos of western landscapes that were inspired by a boyhood trip to Yosemite. He won three Guggenheim grants to photograph the national parks (1944–58). Founding the f/64 group with Edward Weston in 1932, he developed zone exposure to get maximum tonal range from black-and-white film. He served on the Sierra Club Board (1934-1971).

This video (larger top window), begins with Adams explaining his competing interests of music & photography, and then touches major events in his career, run time: 4:11.

Below (smaller window) is the complete unedited version, run time: 13:45.

Lumière was proud to feature Adams’s work in our inaugural exhibition – Pirkle Jones and Friends, Jones served as his first technical assistant, their association continued over four decades. Additional information can also be found on his artist page.

Ansel Adams: A Legacy - @ Booth Museum

September 25, 2010 – March 13, 2011

Showcasing more than 130 photographs by famed photographer Ansel Adams, including his most iconic images. The depth, breadth and quality of this exhibition was exceptional.

These photographs were considered by Adams to be some of his “best” prints, they were meticulously produced by the artist himself and given to The Friends of Photography. Adams was one of the founders of this organization, that began in 1967, with the aim of promoting creative photography and supporting its practitioners.

The newspaper clipping is from the Monterey Herald, December of 1970, courtesy of Steve and Sue James/Eikon Gallery. It illustrates Adams’ commitment and support of the Friends of Photography.

More information on current Booth programing visit:

The Booth Western Art Museum web site.

The Booth is located in Cartersville Georgia, (28 miles north on I-75, exit 288).