Edward Weston

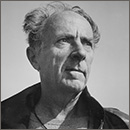

Edward Weston (1886 – 1958)

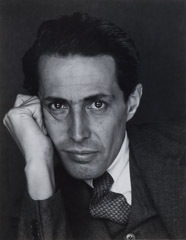

Weston was born in Highland Park, Illinois on March 24, 1886. He was given his first camera, a Kodak Bull’s-Eye #2, for his 16th birthday, when he began taking photographs. His favorite hangouts were Chicago parks and a farm owned by his aunt. Weston met with quick success and the Chicago Art Institute exhibited his photographs a year later, in 1903. He attended the Illinois College of Photography. In 1906, Weston moved to California, where he decided to stay and pursue a career in photography. He had four sons with his wife, Flora May Chandler. Weston opened his first photographic studio in Tropico, California (now Glendale) and wrote articles about his unconventional methods of portraiture for several high-circulation magazines. In 1922, Weston experienced a transition from pictorialism to straight photography, becoming “the pioneer of precise and sharp presentation”. His pictures included the human figure as well as items of nature, including seaside wildlife, plants, and landscapes. Tina Modotti, his professional (and romantic) partner, often accompanied him to Mexico, creating much gossip in the media.

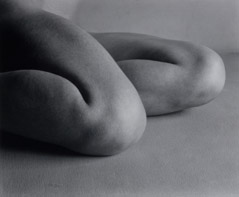

After 1927, Weston worked mainly with nudes, still life — his shells and vegetable studies were especially important — and landscape subjects. Henrietta Shore was a companion in the 1930s; her paintings influenced him to photograph her shells.[2] After a few exhibitions of his works in New York, he co-founded Group f/64 in 1932 with Ansel Adams, Willard Van Dyke and others. The term f/64 referred to a very small aperture setting on a large format camera, which secured great depth of field, making a photograph appear evenly sharp from foreground to background. Weston also achieved great sharpness by not enlarging. He made contact prints from his 4×5″ or 8×10″ negatives. The detailed, straight photography that the group espoused was in opposition to the pictorialist soft-edged methods that were still in fashion at the time. In 1937 the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation awarded Weston a fellowship, the first given to a photographer. In 1939, he married his assistant, Charis Wilson, with whom he had lived since 1934. They divorced in 1945. During this time he received exclusive commissions and published several books, some with Wilson, including an edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass illustrated with his photographs. He also produced some of his few color photographs with Willard Van Dyke in 1947. Weston also collaborated on several volumes of his photographs with photography critic Nancy Newhall, beginning in 1946. The Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson houses a full archive of Edward Weston’s work.

Select This Link to view an additional 14 minute video of Brett, Cole & Neil Weston video (above, right – 14 minute) on the Lumiere Vimeo page.

The work of Edward Weston is featured in these exhibitions.

(Select the image to view the exhibition page)

The work of Edward Weston is featured in these Theme Collections.

(Select the image to view the theme page)

AJC, The Lens Of A Giant

Below is an excerpt of a review from the Atlanta Journal and Constitution.

To read the entire review please access the AJC web site.

DATE: October 7, 2007

PUBLICATION: Atlanta Journal-Constitution

BYLINE: CATHERINE FOX

TITLE: The Lens Of A Giant

EXHIBITION: The Weston Legacy

Atlanta Celebrates Photography is always a great opportunity for exposure (forgive me) to contemporary photography. This year, more than in fests past, brings 20th-century masters to the fore.

“Loving/Longing,” an icon-packed group exhibition opening Thursday at Agnes Scott College, casts a wide net of American and European greats. For depth of focus, there’s the High Museum’s presentation of Harry Callahan’s photos of his wife Eleanor and “The Weston Legacy” at the Atlanta gallery Lumière.

Although the Lumiere show honors a family of photographers, its center is, inevitably, the patriarch. Edward Weston is, after all, one of the giants of “straight photography.” Many of the memorable images in this show are embedded in our cultural consciousness, and they exerted a profound influence on ensuing generations.

Weston came of age artistically when photography was flexing its muscles as an art form. Disavowing pretensions to painting, practitioners on several continents championed the clarity and realism that they felt represented the medium’s unique character.

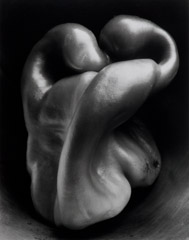

Together with the like-minded West Coast artists in Group f/64, Weston took up the call. In nudes, nature studies and California landscapes, he sought to render “the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself.”

To that end, he depicted objects isolated and free of distractions. The velvety black void in which “Shell’s” (1927) nautilus floats accentuates its shape and the crisp details he was able to record with his 8×10 view camera. It becomes the very shellness of shell.

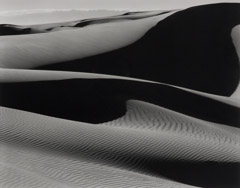

But “straight” did not always mean straightforward. Weston often presented the dunes, the shore, the rocky hills of his beloved landscape shorn of context — an anchoring horizon line, say — so that the photos teeter between reality and abstraction.

A combination of high vantage point, spatial ambiguity and crystalline clarity in “Surf, Point Lobos” (1938) turns the vista of sea crashing on the shore into a yin-yang of light and dark.

And realism doesn’t mean nothing but the facts. Out of time, and context, still as a Byzantine icon, his images simmer with spirituality, animism almost.

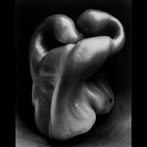

But they are earthy, too: This is an artist who managed to make a disembodied pair of knees sexy, not to mention a cabbage leaf. In said close-up, the languid leaf suggests the drape of lingerie to come-hither effect. Just to be sure you don’t miss the point, Lumiere juxtaposes his femme fatale “Pepper” with a series of his nudes.

Vast and intimate, gorgeous and sober, sensual and spare, the best of these photos explain Edward Weston’s place in the pantheon and the high bar he set for the photographers who followed.

Bottom line: A great opportunity to spend time with a master.

The Weston Legacy

Atlanta History Center

A lecture and presentation on the history and legacy of the photography of the Weston family, was followed by a panel discussion with several experts. Panelist included: Julian Cox, Curator of photography at the High Museum of Art, photographer and art collector Lucinda Bunnen, and Asheville photographer, Tim Barnwell.