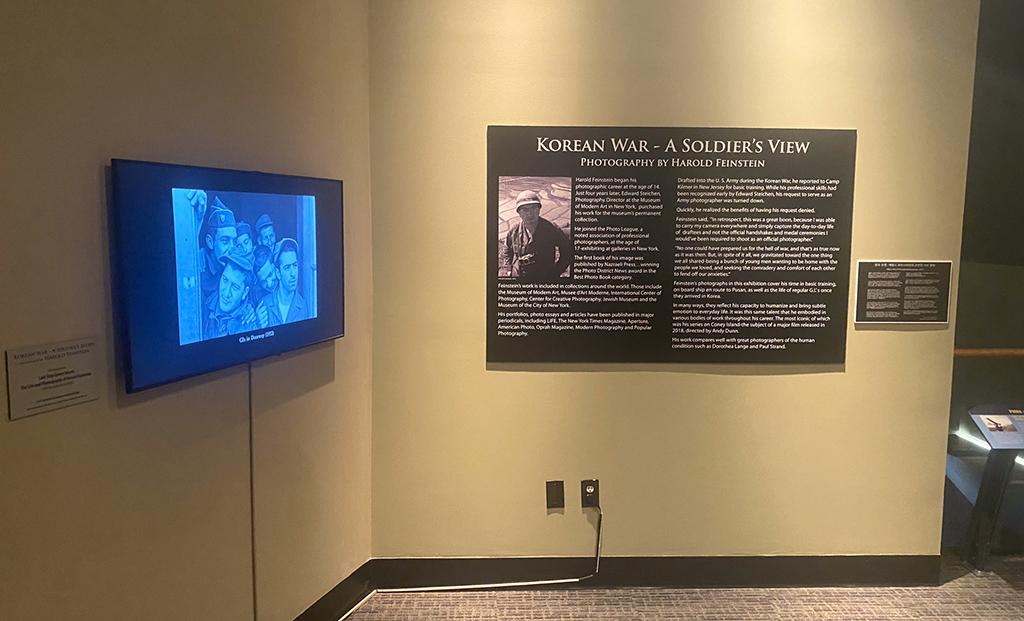

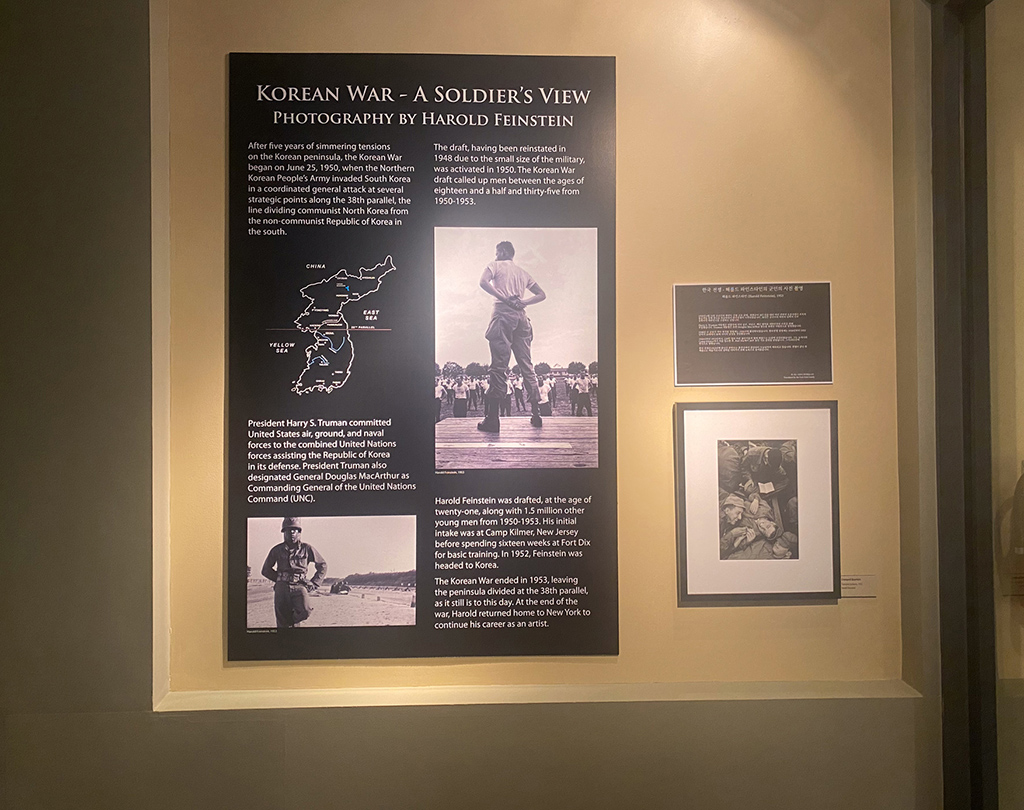

When Harold Feinstein, then a young photographer from New York, was drafted for the Korean War, he applied to be an official Army photographer. Even at this tender age, Feinstein’s abilities as a photographer had been recognized by some of the most influential curators in the United States, including Edward Steichen of the Museum of Modern Art.

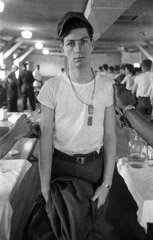

The Army, however, must not have shared Steichen’s view as his request was denied, and Feinstein was sent to Korea in 1952 to fight as an infantryman on the front lines. From his first day at Camp Kilmer for induction, at Fort Dix NJ for basic training, during the long ocean voyage to Korea, and during his time there, Feinstein realized the benefits of not being an official Army photographer.

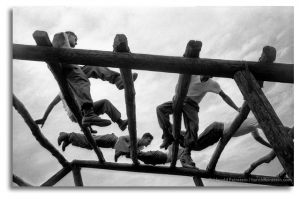

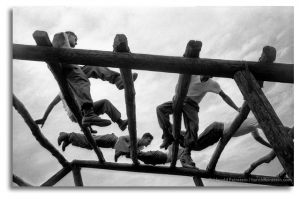

Confidence Course, 1952

Feinstein wrote how lucky he came to feel that his wishes had been denied by the Army. “In retrospect, this was a great boon, because I was able to carry my camera everywhere and simply capture the day-to-day life of a draftee and not the official handshakes and medal ceremonies I would’ve been required to shoot as an official photographer.”

Feinstein suffered a non-combat related injury after a few months on the front lines and was sent back to Pusan (after a stint in a Kyoto hospital) to spend the rest of his tour as a sign painter and illustrator at Army Headquarters away from heavy combat. This location gave him even greater access to the Korean people, as well as an independent view of the day to day lives of GIs and civilians alike.

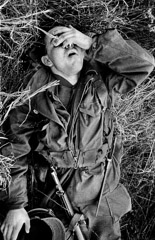

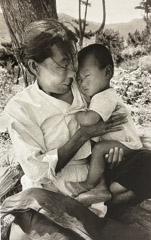

Standing Guard, 1952

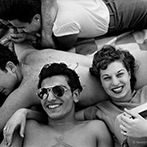

“As I look at these photographs now I see again through the eyes of a 21-year-old from Coney Island, fresh off the boardwalk and thrown into a situation with my peers who could’ve been at Coney Island with me riding the cyclone or flirting with their girlfriend under the boardwalk, or cruising around town on a Saturday night. No one could have prepared us for the hell of war, and that’s as true now as it was then. But in spite of it all, we gravitated toward the one thing we all shared – being a bunch of young men, wanting to be home with the people we loved, and seeking the comraderie and comfort of each other to fend off the anxiety of going to war,” he wrote.

It seems fitting that Feinstein brought back humanizing pictures from Korea, since that conflict is sometimes referred to as “America’s forgotten war”. Feinstein never forgot the war, nor the price paid by Americans and Koreans alike. Standing Guard, Korea, 1953 is a stark image of an American soldier protecting a desolate stretch of road on a rainy day. Like the solider, the viewer’s ability to see down this foggy road is obscured, perhaps reflecting Feinstein’s feelings about this war that claimed the lives of well over 36,000 American soldiers.

According to the data from the U.S. Department of Defense, the United States suffered 33,686 battle deaths, along with 2,830 non-battle deaths. South Korea reported some 373,599 civilian and 137,899 military deaths. Western sources estimate the Chinese army experienced about 400,000 killed and 486,000 wounded, while the North Koreans suffered 215,000 killed and 303,000 wounded.

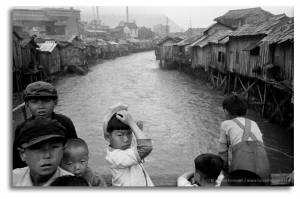

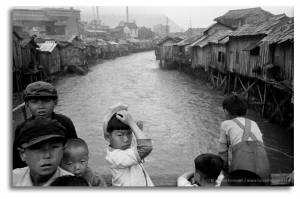

Korean Children on Village Bridge, Pusan, 1953

Though Harold Feinstein passed away in June of 2015, one of his blog posts from 2014 recounts his feelings about his military service and the Korean War in general.

“As a GI, I remember arriving in Pusan and receiving instructions not to ‘fraternize’ with the local people. But, I confess that I broke that rule. I…got to know the local children. I also witnessed their sacrifices and suffering,” he wrote. “(I) remember, with great fondness and sympathies, those GIs who were conscripted with me and those civilians who I came to know. I respect them now as I did then.”

Korean Children at Bridge, Pusan, 1953 is a compelling photograph that both depicts an everyday scene of children congregating on a local bridge. It also captures their uncertainty at seeing a western soldier in their midst. The shacks that line the river in this image point to their poverty, but also reveals the intimacy with which Feinstein looked at the country.

A viewer can easily tell that Feinstein was standing among the children, when the image was made. He was not surveying them from afar. His physical proximity is an extension of his closeness to the Korean people.

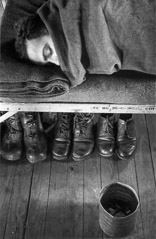

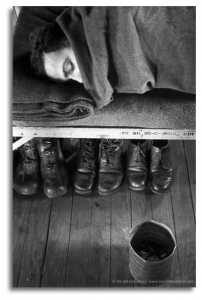

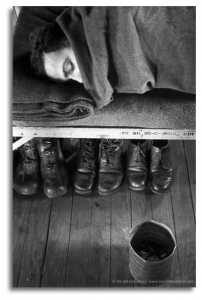

Boots Stowed Under Cot, 1952

Other Feinstein photographs taken in the United States during basic training and on leave, reveal a similar closeness and empathy for American soldiers. In Boots Stowed Under Cots, 1952, a young soldier rests in the barracks, appearing vulnerable under his blanket deep in sleep. This picture foreshadows the powerful series made by Tim Hetherington of American soldiers sleeping in their makeshift quarters in Afghanistan more than fifty years later.

Feinstein acted as both an active member of the United States Army and independent eye. Today’s “imbedded” photojournalists would love to have the access that Feinstein carved out for himself in Korean through his own ingenuity and force of personality.

These photographs of the Korean War are one of many ways Harold Feinstein contributed to the history of photography. An online gallery of Feinstein’s images drawn from the course of his entire career can be seen on his

Lumière Artist Page.