500 Years In The Making

Featuring Photography by Tim Barnwell & Thomas Neff

Lumière’s exhibition Southern Heritage – 500 Years In The Making uses photography as a metaphor for the Heritage of the American South.

It reflects the intersection of Christianity & Islam; European Aristocracy & Commoners; Colonists & Native Peoples; Agriculture, Arms & Disease; Tolerance & Intolerance. One of unintended consequences from the interaction of people, animals, plants and microbes.

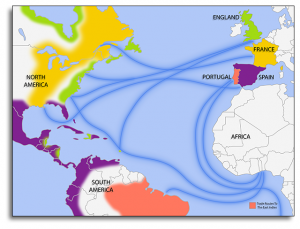

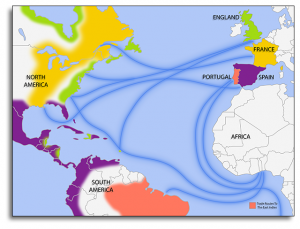

Trade Routes, (circa 1670-1730)

The starting point is 500 years ago with the birth of Henry VIII and Columbus’ discovery of Hispaniola. At that time, “the Muslim world was larger, wealthier, more powerful and more scientifically advanced.”1 The Europeans’ ambitions led them around the cape of Africa to the “East” Indies and across the Atlantic to discover the “West” Indies: then to the main lands. The map illustrates the extensive trade routes that evolved.

In the Americas, it began a 200 year period of Spanish colonial occupation of Florida. The French yielded to the Spanish in favor of Canada and the Mississippi River territories… opening the door for the English on the Atlantic coastline north of Florida.

By the time Raleigh and Smith arrived in Virginia, there were 2.2 million native peoples who had occupied North America for some 15,000 years. Theirs was a successful, geographically dispersed society. One with extensive trading arrangements…and almost 375 languages.

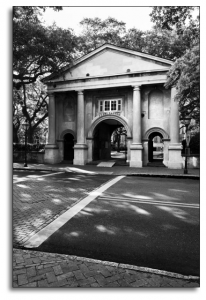

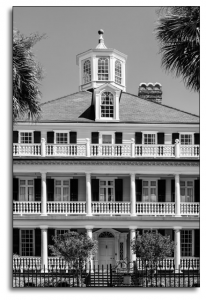

English colonization was sparked by merchant promoters. Shown below is the skyline of Charleston… founded in 1670 by planters from Barbados.

Skyline – Charleston, South Carolina

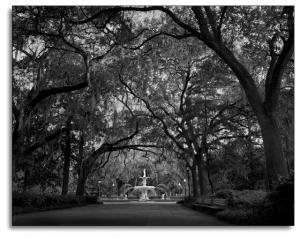

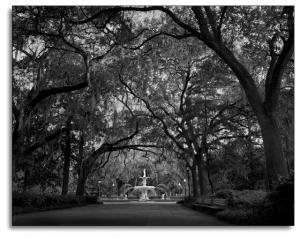

In 1733, Oglethorpe founded the Georgia Colony at Savannah. It became the first planned city in the U.S. with some 20 parks. The colony was the only one to ban slavery, focusing instead on “charity colonists”.

Forsyth Park, Savannah, Georgia

What was an economic boom for Europe was a disaster for Native Americans due to aggressive exploitation. When disease decimated European indentured servants and native Indian slave labor, it led to expansion of the African slave trade dominated by the Portuguese and English, with New England also profiting greatly.

The struggle for land, labor and capital influenced the development of the Caribbean, and later the American South. This new economy was driven by the demand for tobacco, sugar, rice, timber and clothing in Europe. It was reinforced by ship building and the carry trade of New England.

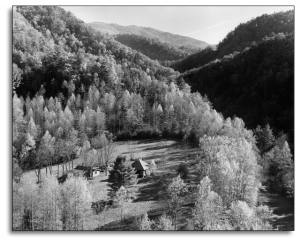

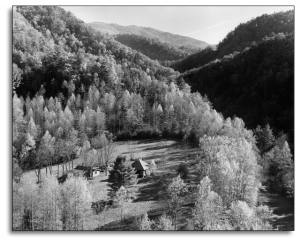

Mountain Farm, North Carolina

As colonists moved inland – first to the Piedmont, then to Appalachia – a new backcountry culture evolved – including interaction with the Cherokee and other tribes.

The exhibition tells the story of the Indian Civilization, Explorers & Colonists, Conflict, Commerce, Religion and Art… as well as the Colonists as Pioneers.

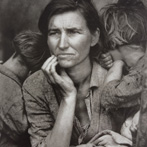

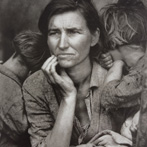

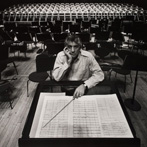

Featuring the photography of Tim Barnwell and Thomas Neff. Also including works by Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange, Peter Sekaer, Berenice Abbott and Arnold Newman.

1 Source: Alan Taylor, University of California

500 Years In The Making

Featuring the work of Tim Barnwell and Thomas Neff – also included is work from Master Photographers who traveled to the south in the 1930’s & 40’s.

Select the image below to view the complete artist page for these photographers.

Tim Barnwell

Thomas Neff

Edward Weston

Peter Sekaer

John Gutmann

Dorothea Lange

Arnold Newman

Berenice Abbott

American history, as described by European settlers and their descendants, is often couched in terms of discovery, though native peoples arrived in the Americans many thousands of years before Europeans.

At the end of the last Ice Age, tribes crossed the Bearing Land Bridge, which connected Asia to the Americas approximately 15,000 years ago. Scientists believe at this time, the Bering Land Bridge was a 600-mile wide region linking Siberia and Alaska. Once filled with small shrubs, which could be used to fuel fires and sustain human life, the Bering Land Bridge now lies underneath the waters of the Bering and Chukchi Seas.

The Indian Confederations of the South were part of this 15,000-year-old American civilization. The largest of these, the Mississippians, occupied a wide expanse from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean for a thousand years. These industrious peoples constructed towns with plazas and earthen mounds surrounded by defensive fortifications made necessary by wars with regional tribes. The prime mound was usually topped by a temple for ritual and was the residence for the tribe’s chief.

Etowah Indian Mounds

One of the best examples of these mounds is the 54 acre Etowah Indian Mounds in Bartow County, Georgia, that was once home to several thousand Indians from 1000 AD to 1550 AD. According to the State of Georgia park service, the Etowah Mound is the most intact Mississippian site in the southeast and encompasses six earthen mounds, a plaza, village site, and a defensive ditch. By the time Hernando de Soto travel through the area in 1540, archaeologists generally agree that the Mississippian culture was in decline and the Etowah Mounds site was abandoned.

Mississippians tended to be small farmers who lived near rivers, which provided water and nutrients for crops. The social structure of these communities usually revolved around elites and commoners. However, social standing was not based on wealth and military power, as much as spiritual beliefs held dear by the tribes. Elites, like the chief and his family, were thought to have descended from deities such as the sun god, and therefore possessed unusual supernatural powers.

The Gaules, a branch of the Mississippian nation, occupied the area around the sea islands of Georgia and Carolina. It was the Gaules who welcomed French explorer Jean Ribault in 1562 at Parris Island, which is now part of South Carolina. Ribault, a protestant, played an important role in colonizing the southeastern region for France.

Two years after the landing at Parris Island, Ribault took command of Fort Carolina, a French colony in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. A larger Spanish force soon landed a few miles south near modern day St. Augustine, marched on Fort Caroline during a hurricane, easily destroyed the fledgling French outpost. Now the Spanish ruled over the land of the Gaules.

Gaule Village Site, on Darien River

The British also desired this strategically located land. In 1661, a Gaule village at a Darien River site was destroyed by Westo Indians (allies of the British) in order to drive out the Spanish.

Eventually the Gaules came into conflict with Spanish missionaries. There was a general insurrection in 1597 during which most of the missionaries were killed and the missions destroyed. This led to the Spanish settlement with England in the “Disputed Territory” that is now Georgia. The Westos themselves were later driven from their village at the navigation head of the Savannah River (near what is now Augusta) by the Shawnee.

Like so much of American history, a look beneath the surface reveals a complicated and fluid world. For example, policies regarding treatment of the Indians by the Spanish, the French and the English were not uniform. Different European powers managed the Indians in ways driven by their individual economic interests and cultural beliefs.

The Spanish

Sailing under a commission from Queen Isabella of Spain, Christopher Columbus landed on the island of Hispaniola in 1492 and claimed the land for the Spanish Crown. When word reached Isabella, she immediately decreed that the natives were her subjects and were morally equal to all her other subjects including Spaniards. The Indians were to be treated humanely, without slavery, but she demanded they be converted to Christianity and taught European ways.

Columbus immediately disregarded her decree, and these Caribean Indians were treated as prisoners of war, forced to work and even to pay tribute – giving gold and other valuables – to the Spanish.

Some influential Spanish clergymen found these policies abhorrent, and tried to work out a more peaceful and just way of converting the Indians.

The Spanish built a mission system in the new world. “Beginning in the middle years of the sixteenth century, Spanish priests, with the support of the Crown, began to establish supervised communities in frontier areas. A few priests would go into an area, learn the local Indian dialect, and begin to preach the gospel. They would persuade the Indians to build a village, accept Christianity, and settle into a sedentary life. The process was extremely dangerous and sometimes the friars lost their lives; however, they often succeeded,” according to historical documents quoted in The Encyclopedia. By 1675, the Spanish ministered to 20,000 Indians at 35 missionaries in the Southeast.

However, the Spanish also treated the Indians with great brutality, compelling them to work as slaves, until their dwindling numbers, forced the Spanish to import slaves from Africa.

The English

The English settled Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 and Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620, almost a century after the Spanish made their first permanent settlements in the New World. However, like the Spanish, the settlers were faced with co-existing with the Indians.

The English tried to trade trinkets, firearms and blankets with the Indians in exchange for furs. They also tried to buy land from the Indians, but since the Indians did not believe in a system of ownership and exchange of title, these attempts failed. In the. Indians had a spiritual relationship with the natural world – they did not think the earth was built for mankind to tame and parcel out in tracts.

Eventually, like the Spanish, the English tried to enslave the Indians and convert them to Christianity. However, they were far less successful in these endeavors than the Spanish, for several reasons. Most the English settlers were families, not single men or soldiers like the Spanish, so there was less intermingling of the races. Also the Indians of Virginia and the Carolinas did not die out as quickly as the Caribbean Indians that the Spanish first encountered.

While the English tried to convert Indians to Christianity, they did not go about it with the same ferocity and with an organized system of Missions, as the Spanish did. The English colonists basically set up towns that mimicked their villages back home in England. They did not invite the Indians to come and live with them in these towns. In 1651, the English did establish “praying towns” which were settlements where Indians were encouraged to live like Europeans and embrace Christianity.

The Encyclopedia, a resource that synthesizes original historical sources, gives a succinct account of the British attempts to manage the Indians:

In the English Colonies, the pattern was a succession of trade, attempts to secure land, misunderstanding, and conflict. The result was that the Indians were generally in retreat after the first few decades of the colonial period, especially as the Indians learned that close association with the colonists was likely to result in sickness and death from European disease, like smallpox. Efforts to enslave the Indians were given up fairly early and the effort to Christianize them, although part of the agenda of the early period of colonization, never developed as extensively as it did in Latin America. The most important difference, however, was the absence of intermarriage.

The French

The French colonies in the New World were generally organized around the fur trade, instead of agriculture. This meant they did not view the acquisition of Indian land as critical to their success as did the English. The French moved northward fairly early in the colonial period, as they were outmanned by the Spanish in Florida and coastal Georgia. The French exploited inter-tribal relationships to establish trade with the Huron, Montagnais and the Algonquin along the St. Lawrence River and inland towards the Great Lakes.

There are instances of French land grabs and brutality towards the Indians, such as their enslavement and sale of members of the Natchez tribe in the 1700s. French Jesuits also had some success in converting the Huron tribes to Christianity, though the French did not practice mass conversion as did the Spanish and English. The French colonists are generally considered by historians to be the most humane of the European powers.

The patterns established by the European leaders basically continued as colonists pushed ever westward, seizing or buying land as they expanded. After the American Revolution, the “new” Americans continued their journey towards the Pacific. This expansion guaranteed continual conflict, violence and a population shift favoring colonists, who became independent Americans.

When The United States Congress passed the 1830 Indian Removal Act, it established what was perhaps the most impactful example of Indian mistreatment, as the entire Cherokee nation was forced to leave their land.2 When by 1838 only 2,000 Cherokees had migrated, the U.S. government sent in 7,000 troops, who forced the remaining 16,000 Cherokees into stockades at bayonet point. This began the march known as the Trail of Tears, during which 4,000 Cherokees died of cold, hunger, and disease on their way to the western lands.

2 John Alexander Williams, Western Carolina University

In the early 1700’s, England established a string of forts along the Georgia and South Carolina coast to act as a check on Spanish aggression.

As far back as 1513, Spain had been a presence in Florida, beginning when Juan Ponce de Leon landed near land now called Cape Canaveral and established “La Florida” in the name of the Spanish crown. Ponce de Leon’s arrival took place a mere 21 years after Christopher Columbus first set foot in the Bahamas.

Almost 200 years passed as Spain fought off French Huguenots, built a mission system, which was later destroyed, and battled to subdue the Indians and convert them to Catholicism. As British power grew in the American colonies in the 1700’s, English leaders realized they needed to take measures to protect their assets north of Florida.

Fort King George

Fort King George

By 1721, tensions were rising between Spain and England, which led to the creation of Fort King George in what is now Darien, Georgia. Though long decommissioned, Fort King George is the oldest remaining English Fort on Georgia’s coast. The original structures have been rebuilt.

From 1721 until 1736, Fort King George was the southern outpost of the British Empire in North America. The facility consisted of a cypress blockhouse, barracks and palisaded earthen fort built by Colonel John Barnwell and his men.

The next seven years were marked by terrible hardships, including fire, disease and the threat of attack from both the Spanish and the Indians, as well as a harsh coastal environment. Eventually the suffering was too great and the fort was abandoned by the soldiers. All totaled, 140 men died, though none in battle. The fort itself was formally abandoned in accordance with an agreement signed by Spain and England.

However, General James Oglethorpe brought Scottish Highlanders to the site in 1736 and named it, Darien.

Darien eventually became an important export center for lumber until 1925.

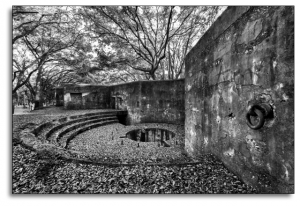

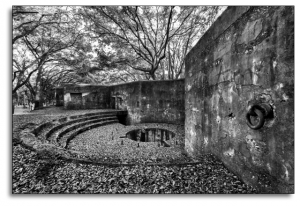

Fort Frederica

Fort Frederica

Meanwhile, Oglethorpe had sailed south in 1734 looking for another military site. He decided that St. Simons Island was strategically located, as it sat on bluffs overlooking an inland river passage. The fort and town were known as Frederica, in honor of Frederick Louis, the Prince of Wales. Tim Barnwell’s photograph of the of the fort today document the remains of its battery and gun positions facing the Frederica River.

Aware that the Spanish saw the new fort as a renewed threat, Oglethorpe felt the need to strengthen his position so, he sailed to England in 1737 and returned a year later with a force of 1,000 men. The fort was filled with colonists from England, Scotland and Germany, in addition to its’ military contingence.

By 1739, the British and the Spanish were at war over the slave trade and fighting swept through the Caribbean and up the Georgia coast to St. Simons. Spanish ships and troops invaded St. Simons Island but were ultimately defeated by Oglethorpe in 1742.

This British victory not only confirmed that Georgia was British territory, but it also signaled the end of a

need for Fort Frederica. When peace was declared, Frederica’s garrison (the original 42nd Regiment of Foot)

was disbanded, and eventually the town fell into decline.

Fort Moultrie

Fort Moultrie

As Charleston Harbor became an increasingly important location for colonial commerce, the British built Fort Moultrie. During the American Revolution, Fort Moultrie proved invaluable as it withstood attack from nine British warships. The soft Palmetto logs that the fort was built from absorbed cannon shot, rather than cracking. Some soldiers even reported seeing cannon balls bouncing off the Palmetto logs.

Following the War of 1812, President James Madison recognized the importance of coastal forts, and Congress created a national sea front network to protect the young country from foreign invaders. Fort Pulaski and Fort Sumter were part of this network which was known as The Third System. These two forts would later play important roles in the Civil War.

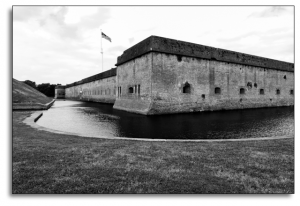

Fort Pulaski

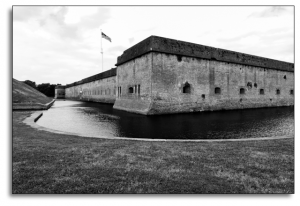

Fort Pulaski

Fort Pulaski was a massive five sided structure whose primary purpose was to protect Savannah from naval attack from its position on Cockspur Island at the mouth of the Savannah River. In 1830, a new West Point graduate named Lieutenant Robert E. Lee headed up the preliminary construction of Fort Pulaski. Lee chose the location and oversaw the implementation of a series of drains and dykes to support the weight of the masonry fort. Lt. Joseph Mansfield soon took over the construction which lasted 14 years.

By the time construction was completed in 1847, the fort boasted 147 cannons, some of which were mounted on the top walls of the fort and some inside casements inside the walls.

In the years before start of the Civil War, Fort Pulaski fell into disrepair, its moat filled with mud and its cannons in place but unmounted. Confederate military forces realized its strategic importance and hurried to return repair the damages using slaves from nearby rice plantations and five companies of troops from Macon and Savannah.

Though Pulaski was repaired in time for battle, its impenetrable appearance proved illusory, and Fort Pulaski fell to Union troops after a siege in 1862. With its new rifled cannons, Union troops were able to blast two 30 foot holes in the southeast side of the fort, and Confederate forces were forced to surrender after just 36 hours. This was a blow to the Confederacy, as the port of Charleston was crucial to the chain of supply.

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter

The name Fort Sumter is etched into American memory as the site of the first shots fired during the Civil War. At the start of the war Fort Sumter was in Union hands, since the South had only recently seceded from the United States in 1680 to form the Confederacy.

Fort Sumter was originally constructed in 1829 as a coastal garrison on an island in Charleston Bay, named after Revolutionary War hero Thomas Sumter. Seventy thousand tons of granite were imported from New England to build up a sand bar in the entrance to Charleston Harbor. The fort was a five-sided brick structure and towered 50 feel over the low tide mark. Though it never reached capacity, Fort was designed to hold 650 men and 135 guns in three tiered emplacements.

Sumter was the site of two important Civil War battles. On April 12, 1861 newly formed Confederate forces forced the Union troops to abandon the fort the next day, by cutting off all contact with the mainland. Civilians watched the battle, reportedly in a festive mood.

During the The Second Battle of Fort Sumter on September 8, 1863, Union troops tried and failed to

re-take the fort. It remained – albeit in ruins – in Confederate hands until General William Sherman

marched through South Carolina in February of 1865.

Fort Fremont

Fort Fremont

In 1898, with the Spanish-American War in progress, Congress authorized construction of Fort Fremont on South Carolina’s Saint Helena Island. In its heyday, the fort covered 70 acres and contained a hospital, barracks, stables, guardhouses, commissary, and many support buildings. Approximately 110 men and officers of the 116th Coast Artillery were garrisoned here. The fort never saw battle and was decommissioned in 1901. Only two batteries and the hospital building remain.

The coastal forts of Georgia and South Carolina played an important role during 200 years of conflict with the French, Spanish and English, and later during the Civil War. Though these forts are no longer active military sites, they remind us of the strategic importance of the Southern coast from Colonial times to the end of the 19th Century.

Economics and power struggles drove the exploration of the new world. Europe’s need for new markets and resources to support commerce were key reasons for the colonization of the Americas by England, Spain and France.

Lumière’s current exhibition Southern Heritage – 500 Years In The Making uses photography as a metaphor for exploring the history of the American South, viewed, in part, through the lens of commerce. This exhibition also looks at other motivations for the founding of the Southern Colonies including religious, political and cultural conflicts.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, England was a minor player in the world of trade dominated by the Spanish, Habsburgs, Persians and Ottomans. Knowledge of England’s place in the constellation of trade with more powerful empires of the time is one key to understanding the economic motivations that led to colonization of the New World.

When Elizabeth I ascended to the throne, the British began to challenge the existing power structure. The Age of Exploration began at the end of the 15th Century and lasted through the 18th. This period was marked by extensive global exploration and the rise of a European culture, including Mercantilism and Colonialism.

Queen Elizabeth I established a model trading company in 1585, called the Barbary Company, which granted England exclusive rights to trade with Morocco for 12 years. Elizabeth also sent her ministers to live in Morocco to cement the relationship and ensure the British advantage. The Barbary Company was a model for the eventual colonization of America.

The emphasis on trade and exploration that began in the Elizabethan era laid the ground work for the establishment of a close economic relationship between England and the Colonies.

Within this environment England and her colonies were part of a complex interlocking economic system that affected the flow of people, products and ideas back and forth across the Atlantic. This parallels the establishment of commerce in the Middle East and Indies.

The commonly held perception that the Colonists were self-sufficient is incorrect. In fact, the well-being of the Colonies was closely tied to England. Between 1700 and 1770 the volume of shipping between the Colonies and the homeland tripled. The Colonies’ economy grew from 4 to 40% percent of England’s Gross Domestic Product.

The economy of the American South was centered on agricultural exploitation of the land, climate, and access to water and labor. This potential attracted capital from London, which was vital to the economies of the Colonies. The commercial foundation of the lowland South was further dependent on the shipping capability of its inland rivers and ocean harbors in locations such as Charleston, Savannah and Beaufort. These port cities played a significant role in the economic cycle of goods crisscrossing the Atlantic between the New and Old Worlds.

The economy of the American South was centered on agricultural exploitation of the land, climate, and access to water and labor. This potential attracted capital from London, which was vital to the economies of the Colonies. The commercial foundation of the lowland South was further dependent on the shipping capability of its inland rivers and ocean harbors in locations such as Charleston, Savannah and Beaufort. These port cities played a significant role in the economic cycle of goods crisscrossing the Atlantic between the New and Old Worlds.

The Carolina Colony and the Georgia Colony operated on two different models of labor. The Carolina Colony was founded by West Indians familiar with a plantation system dependent on large tracts of land. These large plantations required a massive amount of cheap labor to operate. Indentured servants eventually earned their freedom or perished trying to do so; disease wiped out Indian labor, which left African slaves as the eventual primary source of labor in the plantation economy.

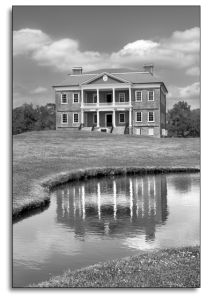

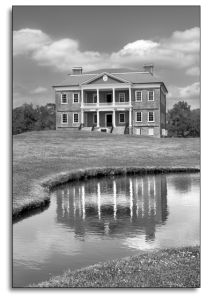

Drayton Plantation, a rare survivor of the Civil War and centuries of natural disasters is a prime example of a slave based economic model. This large rice plantation was founded at the mouth of the Ashley River by John Drayton in the early 1750s. The Drayton family originally ranched cattle but soon realized the value of growing and exporting rice. Historians consider Drayton Hall to be a masterpiece of Palladian architecture.

Drayton Plantation

“Drayton’s palace was the first fully executed example of Palladian architecture in North America; his gardens were composed of idealized English landscapes and the interior spaces were finished with the finest examples of European and Charleston-made material goods, furniture, a wealth of imported ceramics, and fashionable artwork. Taken as a whole, Drayton Hall was one of the most significant elite plantations assembled in colonial America, and its rare survival makes the estate an icon of American history, design, and historic preservation.”1

The Drayton family history in some ways mirrors the larger economic and political role the Colonies began to play within the British system. For example, John Drayton went from being a local farmer to obtaining a seat on the Royal Governor’s Council. He went on to educate his sons in the tradition of English gentlemen. The splendor of the house and gardens was a reflection of the family’s power and prestige.

Cotton, an important cash crop and export, flourished in the Southern Colonies from Maryland to Georgia thanks to the mild winters and sub-tropical climate. Originally cotton would only grow along the coast, which is why some cotton is still known as Sea Island cotton. Later developments in agriculture, led to cotton being planted inland.

The size of the average plantation ranged from 500 to 1,000 acres and produced about 5,000 plants per acre. Cotton exports were not only important in England but also critical to New England’s textile business.

Georgia was founded on a different economic and political model. The English trustees who founded Georgia wanted a colony of many small farms worked by free people. As a result, the trustees provided farms to almost 2,000 “charity” colonists. Others paid for their own transportation drawn by the offer of free land. Georgia was the first and only colony to outlaw slavery, under its original charter written by General James Oglethorpe. However, slavery was allowed in Georgia after the British crown issued an official decree in 1751.

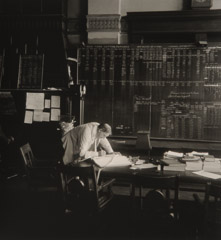

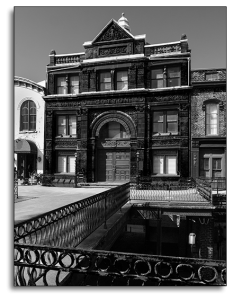

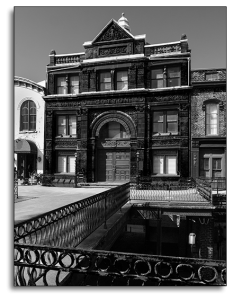

Savannah Cotton Exchange

Shipping and the transfer of goods among the Colonies and across the Atlantic was another important aspect of the economy. Though built after the Colonial period, the Savannah Cotton Exchange is a tangible reminder of just how important cotton was to the overall economy.

The original Savannah Cotton Exchange was built in 1872 when export revenue from cotton was listed at $40 million dollars, and Georgia was the leading cotton producer in the country. The city’s reputation was cemented by the 1880s when the area around the Cotton Exchange was known as the “Wall Street of the South.” The exchange was built to facilitate the needs of planters and cotton brokers as they brought crops to market. The exchange was also a place to congregate and set the market value of cotton that was then exported to larger markets such as New York and London.

The Cotton Exchange was rebuilt in 1886 in the Romantic Revival style and is one of the best surviving examples of this type of architecture.

The commercial foundation of the lowland South was further dependent on the shipping capability of its inland rivers and harbors. Recognizing the importance of safeguarding shipping routes in Georgia, James Oglethorpe, the Governor of the 13th Colony, ordered the construction of the Tybee Island Light House in 1732.

Tybee Island Light House

Though the lighthouse itself has been rebuilt several times after being ravaged by storms, many of the original support buildings are intact. The 1916 version of the lighthouse and the surrounding structures can be visited today. Tim Barnwell’s powerful image of the Tybee Lighthouse guarding the Savannah harbor is a highlight of this exhibition.

While economic success was dependent on cash crops, such as tobacco, rice, indigo, and cotton, the harvesting of timber, was another economic boon for the Colonies and England. Georgia and the Carolinas were full of virgin forests that could be harvested to build ships and other goods. The timber trade also created economic dependence between the Southern and Northern Colonies.

The role that commerce played in the discovery and development in the American South and the growth of European counties has been a key element in Worl History since the 15th Century. The exhibition, Southern Heritage – 500 Years In The Making, Illustrates this role through photographs of the region.

1 draytonhall.org

The founders of the Carolina Colony offered religious tolerance, political representation and land grants as incentives to immigration. The Georgia Colony did this as well. The diversity of the religious faiths and philosophies had much to do with the development of a progressive economic heritage.

The photographs shown in the exhibition include structures built by members of the Jewish, Catholic, Protestant and Church of England faiths. Each group constructed elegant houses of worship consistent with their formal, liturgical forms and the pride they felt in their new country.

DIVERSITY OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

The degree of religious freedom varied greatly from Colony to Colony. Political and economic rationales were often the driving force behind decisions to allow more religious freedom. In many ways, the Southern Colonies were actually more tolerant of different religions than the earliest wave of Protestants – the Pilgrims and the Puritans – that arrived in Massachusetts.

Though both Puritans and Pilgrims were Protestants sects that followed the teachings of John Calvin, the Pilgrims crossed the Atlantic first, forming Plymouth Colony, and were actual Separatists from the Church of England. Puritans (numerically the larger group) disagreed with the English church but did not separate from it. They founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

This distinction is important because it illustrates the nuances involved in the policies that governed the different Colonies. The Pilgrims were more forgiving in their worldview; the Puritans would later be instrumental in wiping out the native population, though the enforcement of harsh religious laws.

Historian Rockwell Stensrud describes the situation in a November 2015 issue of Newsweek, “The Puritans overwhelmed the same Native Americans so helpful to Mayflower survivors. They established towns around Boston and forged a theocracy of magistrates and Congregational clergymen to control the growing population. They hanged dissenters. This ruling elite carried piety on their shoulders and paranoia tucked into their high stockings, distinctive for their pinched lips and the injustices they inflicted on others.”

Meanwhile Charles Town, which was the most important city in the Southern Colonies, allowed Jews, various Protestants of different nationalities and others to settle in the city. Charles Town, now called Charleston, was established in 1670 when three ships carrying 200 colonists sailed from the West Indian Colonies (the most profitable of the British territories) to the mouth of the Ashley River, where they founded the new city in honor of King Charles II.

Though the Church of England was the official church of Virginia and the Carolinas, according to royal charters, the British crown needed to lure more Colonists to act as a buffer against the Spanish Catholic stronghold in Florida. Anyone who was willing to make the journey from the West Indies to the Carolinas was offered religious freedom, land grants and some limited political representation in exchange for relocating.

The original 200 settlers swelled to 6,600 colonists by 1700. Charles Town became known as the Holy City because so many faiths settled there. Sephardic Jews of Spanish and Portuguese ancestry migrated to the city in such numbers that Charleston became one of the largest Jewish communities in North America. In 1824, the Reform Society of Israelites was formed, and Charleston is considered to be the birthplace of Reform Judaism in the United States.

Georgia was founded by James Oglethorpe as a more humane alternative to prison for debtors and to serve as a buffer between the British Colonies and Spanish settlements. Because populating Georgia was a military necessity, religious diversity was encouraged from the time of its founding in 1732. Interestingly its Royal Charter did not recognize the Church of England as the colony’s official church and granted religious liberty to all faiths except Roman Catholics. Settlers included Jews and Presbyterians as well as Anglicans.

The original charter also did not allow slavery, as Oglethorpe envisioned a colony populated by small family farms and craftsmen. Oglethorpe’s progressive views were an extension of his work in England. In 1729, Oglethorpe became a staunch advocate of prison reform when after one of his friends died of smallpox in a London prison because he was unable to pay his jailers for suitable food and shelter.

FAITH REFLECTED IN ARCHITECTURE

Tim Barnwell and other artists photographed many churches and synagogues in Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina for Southern Heritage – 500 Years in the Making. A a few of these religious houses are described below to give readers an indication of the diversity of faiths and architectural styles that can be seen at the gallery. Each photograph in this section of the exhibition documents a church or synagogue that is historically significant.

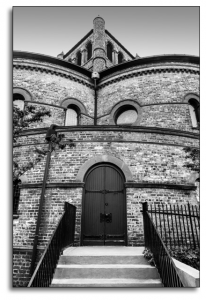

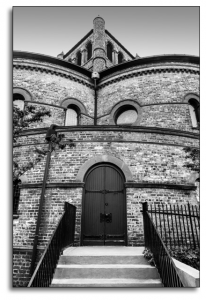

Circular Congregational Church, Charleston

Though the architecture of the Circular Congregational Church, is unique, its beliefs have always been unconventional and sometimes unorthodox. The current building, which is pictured in the exhibition, is the third incarnation of the church. The first two churches were destroyed by war and fire.

Robert Mills, Charleston’s leading architect and designer of the Washington Monument in D.C., built the second version of the church, on which the current building is based. This church was a Pantheon style building that could seat 2,000 people. It boasted the first large dome in America, 7 doors and 28 windows. One observer called it “the most extraordinary building in the United States.”

The first congregation was co-founded between 1680–1685 by English Congregationalists, Scots Presbyterians and French Huguenots. Church members were known as “dissenters” and the church itself was called a Meeting House. During the Colonial period, this unusual church had no official name, but was often called either Presbyterian, Congregational or Independent. For a time, it had no steeple, which many citizens found amusing and odd.

In 1732, a portion of the Presbyterians members left to form the First Presbyterian Church with a stricter adherence to Presbyterian doctrines. The remaining members, which still included some Presbyterians, had a policy that this church “was not so much to define exactly a particular mode of their discipline, and to bind their hands up to any one stiff form adopted either by Presbyterians, Congregationalists, or Independents, as to be upon a broad dissenting bottom, and to leave ourselves as free as possible from any foreign shackles, that no moderate persons of either denomination might be afraid to join them, “ according to church documents.

In keeping with its independent streak and rejection of Anglicanism, the church became a hot house for revolutionary, anti-British sentiment. Prominent members of the Meeting House often called for political and religious freedom from England from the pulpit.

When the British captured Charleston in 1780, this church was harshly punished; many families were exiled to St. Augustine in Florida and later Philadelphia. The remaining families were left destitute in an occupied city. The Meeting House was used by the British as a hospital.

The second version of the Circular Church, described above, enjoyed 40 years of prominence from 1820-1860. The congregation included both white and black members. Unfortunately, a fire ravaged Charleston 1861 and destroyed the church. The Civil War soon followed, delaying repair efforts. In those turbulent days, the black parishioners left in 1867 to form the Plymouth Congregational Church.

The current church is built partly from bricks of the early 19th Century building.

Congregation Mickve Israel, Savannah

Congregation Mickve Israel is one of the most prominent examples of the more tolerant attitude some Southern cities, such as Savannah, took towards religious freedom. In 1733, 42 Jews, the largest group of Jews to land in North America in Colonial days, arrived in Savannah just five months after Oglethorpe established the Colony of Georgia. Most of the people in this group were Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews from Portugal and Spain, who had been living in difficult circumstances in London after originally fleeing the Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834) a decade earlier. Their voyage across the Atlantic was financed by wealthier Jewish members of their community back in London.

The present building is the second incarnation of the synagogue. It was consecrated in 1878, after the congregation outgrew its previous home. The magnificent synagogue was built in a pure neo-Gothic style, which was fashionable in the Victorian era.

When these Colonists first arrived from England, they likely worshiped as a group in private homes, later they met in a variety of temporary structures, until the first synagogue was built in 1818 at the corner of Liberty and Perry Streets; this was the first synagogue in Georgia.

A large wave of German Jewish immigrants began in in 1840. These new settlers swelled the ranks of the synagogue, creating demand for the current larger building.

Congregation Mickve Israel is also important for the role it played in the reform movement.

Saint Cyprians Episcopal Church, Darien

After worshiping on property belonging to Major Pierce Butler on an island near Darien, Georgia, in 1875, a group of freed slaves who were members of this congregation began construction on the present St. Cyprian’s church. The building was consecrated in 1876 and named for Cyprian of Carthage, a martyred African saint of the early church.

St. Cyprian’s is constructed of tabby according to the building methods of mid 19th Century coastal Georgia. It is believed to be one of the largest tabby structures still in use in Georgia. The building suffered extensive damaged in the hurricane of 1896 and by another storm in 1898, but in each case the building was repaired and the congregation continued to worship.

From 1892 through 1914, St. Cyprians was under the direction of the Rev. Ferdinand M Mann, an African American priest of the church. It was during this time that St. Cyprian’s school was established for the education of African American children in Darien. The school served the community for many years, and several of the current members of St. Cyprian’s received their initial education at the school.

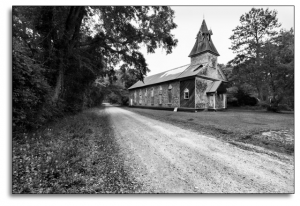

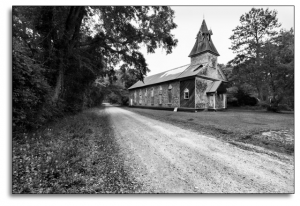

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, McClellanville

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church, built around 1872, is significant as an example of late-nineteenth century vernacular Gothic Revival church architecture. The church also illustrates the growth of the A.M.E. Church among freed slaves in Reconstruction-era South Carolina. Bethel A.M.E. was the first African American church in the town of McClellanville, South Carolina. It is on the National Historic Register.

This rectangular building, features an unusual pediment and a gable roof that supports a square (at its base) steeple. Pointed Gothic arches with chevron wooden panels cap each window. The church cemetery, with tombstones dating from the 1880s to the late twentieth century, also contributes to the historic character of the property. Some windows and all transoms retain the original colored panes; most of the windowpanes were replaced in 1989 after Hurricane Hugo.

Christ Church, Frederica

Christ Church in Frederica dates to 1736 when Anglican minister John Wesley preached at St. Simon’s Island on the Georgia coast soon after General James Oglethorpe and his band of settlers arrived there. The first parishioners met in private homes, as a variety of factors including The Revolutionary War and the War of 1813 prevented them from erecting a small church until 1820.

Union forces destroyed most of the original church during the Civil War and this small group was again forced to worship in homes until the current building was constructed in 1884 around the remains of the original alter.

Symbolism is literally built into church architecture, as local shipbuilders constructed the new building in a cruciform shape resembling an inverted ship’s hull, suggesting that faith is a ship or a voyage. Christ Church is a Gothic style building featuring a tall belfry and a number of stained glass windows that recount events in the life of Christ, the history of the church and St. Simon’s Island.

One window depicts John Wesley preaching at Frederica under live oak trees. Wesley founded the Methodist faith after leaving St. Simon’s and returning to England. Methodism is part of a larger evangelical movement, known as The Great Awakening, that spread through England and the American Colonies in the early 19th Century.

Churches that grew out of the Great Awakening preached Christian doctrine through parables that ordinary people could relate to. The most charismatic features were revivals, drone like singing, chants and African slave work song formats conducted in the “call and response” style.

The Walnut Methodist Church in North Carolina, which can also be seen in this exhibition, symbolizes this movement as it expanded west.

As the agricultural and shipping industries grew, a wealthy class of planters and merchants flourished in Charleston, Savannah and other Southern towns. Trans-Atlantic trade brought more than goods from London, it also brought culture and ideas about architecture, education and the fine arts. These entrepreneurs built grand mansions and cultural institutions as a legacy of their achievement and as a service to the public.

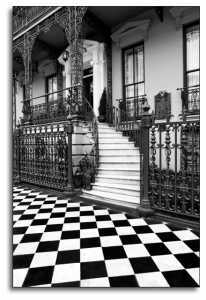

Tim Barnwell’s meticulous black and white photographs of Charleston’s and Savannah’s historic architecture enables viewers to imagine what these modern cities looked like in an earlier time. Though many of the buildings seen in the exhibition are the second or third incarnations of their originals, the remaining and rebuilt institutions and homes still reveal the past. Barnwell’s dramatic panorama creates an overall impression of the past and present co-existing.

Colonial, Georgian and Federal styles were dominant in Charleston until the advent of the Civil War when other architectural modes came into vogue. Colonial structures are known for low foundations and few windows; Georgian style features boxed chimneys and raised basements; balconies, staircases and fan lights mark the Federal style.

Though Charleston’s historic buildings are too numerous to consider individually, some of the most prominent examples are discussed here.

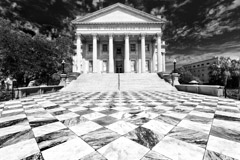

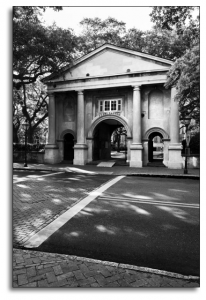

College of Charleston

Founded in 1770, The College of Charleston is the oldest college in South Carolina and the first municipal college founded in the United States. However, by 1864, the Federal bombardment of the city destroyed much of the original architecture. Charleston lay in ruins. Three of the college’s historically important buildings, the Main Building, Library and Porter’s Lodge were built in the Roman Revival style, during and after the Civil War.

The Roman Revival style is based on 11th and 12th Century Romanesque architecture but features simpler arches and windows. The original Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C. is a famous example of Roman Revival. This style was also a popular choice for colleges constructed around the time, including the College of Charleston.

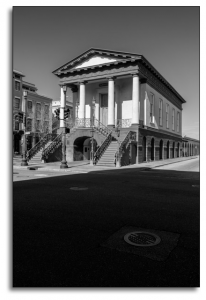

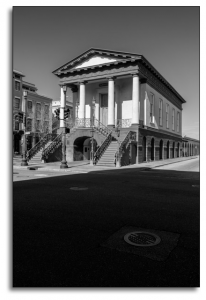

Charleston City Market

The Charleston City Market, though renovated several times, can be seen today, much as it was in the 18th Century, as a series of low sheds anchored by Market Hall, a Greek Revival building that is perched on top of an arcade. Several prominent citizens donated the land in 1788 with the stipulation that it always be used as a market. Though slaves and poor whites shopped for meat at the original structure, the Charleston City Market was not used to sell slaves, as is commonly believed.

Dock Street Theatre

Charleston’s Dock Street Theatre was the first building in America constructed exclusively as a theater. The Recruiting Officer, a 1736 work, was the first play performed in this historic setting. Like many original buildings in Charleston, the first Dock Street Theatre was most likely destroyed by the Great Fire of 1740. After that, the site was used as a hotel and for other purposes. The Historic Dock Street Theatre reopened for the third time on March 18, 2010, after a three year, $19-million-dollar renovation by the City of Charleston. The theatre is now home to over 100 performances a year, including the Spoleto Festival.

Charleston Museum

Charleston can boast of another first – the Charleston Museum. Founded in 1773, the Charleston Museum is considered to be the first museum in America. According to the museum web site, “Inspired in part by the creation of the British Museum, the Charleston Museum was established by the Charleston Library Society on the eve of the American Revolution and its early history was characterized by association with distinguished South Carolinians and scientific figures including Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Thomas Heyward, Jr., Reverend John Bachman and John J. Audubon. First opened to the public in 1824, the Museum developed prominent collections, which Harvard scientist Louis Aggasiz declared in 1852 to be among the finest in America.”

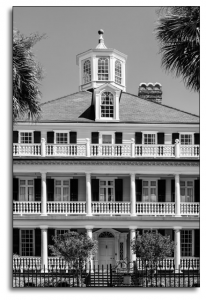

The Battery

Originally the Battery was a fortified seawall at the southern tip of the Charleston peninsula where the Cooper and Ashley Rivers meet. Though this was an important military site, eventually it gave way to a district of historic antebellum homes with views of Fort Sumter, Castle Pinckney and Sullivan Island’s Lighthouse. The battery is known for its many architectural gems including widow’s walks, which were typical of Italianate architecture of the 19th century coastal areas. Supposedly the wives of sea captains would scan the horizon from these vantage points, searching for their husbands.

Private Homes

Cabbage Row, a group of pre-Revolutionary War buildings at 83 and 85 Church Street was the inspiration for Catfish Row, the setting of Ira Gershwin’s opera, Porgy and Bess. The opera is based on Dubose Heyward’s 1925 novel, Porgy. Heyward was a Charleston native who lived nearby on Church Street.

Just to the right of the Church Street house is the 1763 home of John Rutledge a governor of South Carolina and a signer of the Constitution. This home is now the only hotel in America where a signer of the Constitution once lived. Rutledge designed the house as a wedding gift for his bride, Elizabeth Grimke. As chairman of the drafting committee, Rutledge wrote several versions of the Constitution in the 2nd floor drawing room. George Washington visited the home in 1791, enjoying breakfast there with Mrs. Rutledge during a presidential visit.

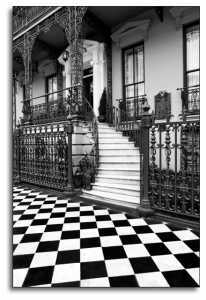

Urban Design of Savannah

Savannah was the first planned city in the United States. General James Oglethorpe laid out the city according to a ward system. Four residential blocks and four commercial blocks were set around a central square, which was the nucleus of every neighborhood. Each residential block contained 10 homes. Outside the town limits, each family home was assigned a square mile tract of land for farming.

Oglethorpe created this new city based upon the ideals of the Enlightenment, including science, humanism, and secular government. Oglethorpe imagined the new Colony would be a place of social equity and civic virtue, which is why he allocated land for housing and farming in equal increments, as well as a prohibition on slavery.

The City of Savannah has preserved the ward design within its National Historic Landmark District, though eventually 18 wards were added to the original six, to total the 24 wards that exist today. The city’s modern street grid outside of the historic district follows much of the original system of rights-of-way established under the Oglethorpe Plan for the gardens, farms, and villages that made up the Savannah region.

Savannah Mansions, seen in the exhibition, showcase ornate European style and craftsmanship in iron work, masonry and carpentry. These details reflect Oglethorpe’s vision for his colony.

The photographs in this section of Southern Heritage – 500 Years In The Making reveal the wealth from commerce, the influence of the arts, as well as the diversity of national cultures that are inherent in the founding of Charleston and Savannah. The row houses and mansions of Charleston and formal urban design that Oglethorpe created for Savannah, with its 20 plus parks, show the importance of the close Colonial ties to London.

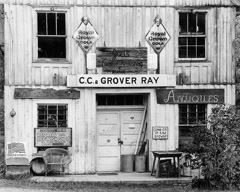

Western expansion is a story of land speculators, ambitious politicians, farmer Colonists and Indian tribes, particularly the Cherokee nation. Starting at the Marshes of Glynn, the subject of Sydney Lanier’s famous poem, Colonists moved West to seek opportunity on lands purchased or granted to them when they fulfilled their contracts and were no longer indentured servants. Newer immigrants and free people were also part of this movement.

These newly minted pioneers ventured first into the Piedmont region, then to the mountains and eventually all the way to The Pacific Ocean. During the time of the French and Indian Wars, 1754-63, the Appalachian Mountains were considered the frontier.

For decades, artists, writers and social scientists have perpetuated a stereotype of Appalachia as an ignorant, impoverished and backwards culture. Visiting photographers were commissioned by the federal government to propagandize New Deal policies and programs in the 1930s. Many of the images they created laid the ground work for a continually lopsided depiction of Appalachia.

The initial settlers were self-sufficient and relied on their families for labor. They learned how to hunt and survive in a sometimes hostile environment from their Indian neighbors. Beginning in 1790, a series of treaties with the Cherokee and other tribes opened land to farming interests promoted by land speculators.

Development was accelerated by land grants issued during the North Georgia “gold rush” and robbed the natives of their land. The last of the treaties, advocated by President Andrew Jackson, passed by the U. S. Congress in 1830 by only 1 vote. It was devastating for the Cherokee, leading to the infamous “Trail of Tears” forced relocation from their Appalachian lands to Oklahoma. Only a few Cherokee of that era survived by hiding in the mountains.

By 1860, more than ten percent of the population of Appalachia was of African-American descent. After the Civil War, some former slaves settled here, though most continued on to the North. Berea College in Eastern Kentucky admitted students of all races from its inception in 1867, and its first class contained 96 African-American students and 91 white ones.

The photographs included here illustrate the heritage of music, crafts and farm life that continues to this day. Regional singing groups and musicians are keeping alive the traditional Appalachian ballads, which descended from Anglo Celtic music brought by early white settlers. These ancient imports from the British Isles have been influenced by traditional Cherokee and African songs.

Though in popular music, a ballad can take many forms, a traditional Appalachian ballad is usually sung unaccompanied. Dance music, such as the Irish reel, is often played with the fiddle. Other traditional instruments include the the banjo, mandolin, fretted dulcimer and guitar. The banjo is actually an African instrument, brought to the New World by slaves in the 18th Century.

Most of these photographs were made by Tim Barnwell over a period of 35 years. Norton Press published three distinguished volumes of Barnwell’s work, On Earth’s Furrowed Brown, The Face of Appalachia and Hands in Harmony. Barnwell is not an outsider, interested in the failings of Appalachia, but rather a native son with a nuanced view. His images offer a clear-eyed and compassionate look at this misunderstood culture.

The economy of the American South was centered on agricultural exploitation of the land, climate, and access to water and labor. This potential attracted capital from London, which was vital to the economies of the Colonies. The commercial foundation of the lowland South was further dependent on the shipping capability of its inland rivers and ocean harbors in locations such as Charleston, Savannah and Beaufort. These port cities played a significant role in the economic cycle of goods crisscrossing the Atlantic between the New and Old Worlds.

The economy of the American South was centered on agricultural exploitation of the land, climate, and access to water and labor. This potential attracted capital from London, which was vital to the economies of the Colonies. The commercial foundation of the lowland South was further dependent on the shipping capability of its inland rivers and ocean harbors in locations such as Charleston, Savannah and Beaufort. These port cities played a significant role in the economic cycle of goods crisscrossing the Atlantic between the New and Old Worlds.