Circle Of Light

As photography concerns the recording of light, this exhibition is about the small circle of

Master Photographers who led the development of it in the 20th Century.,

Featuring Photographs By:

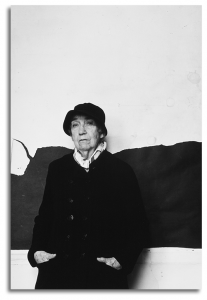

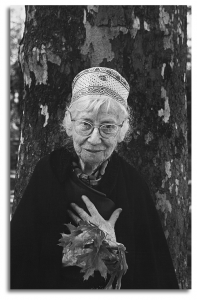

Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976)

Among many honors, Cunningham was a Guggenheim Fellow, Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and recipient of an honorary doctorate of fine arts, acknowledging her seven decades of leadership in photography. She began this journey at the University of Washington. Imogen’s interest in photography led to her study of “Chemistry and Scientific Photography.” She won a post graduate fellowship for study in Dresden, Germany, under the direction of Prof. Robert Luther. There, she continued her study of chemistry and understanding its effect on photographic printing.

Returning to Seattle, she visited Alvin Langdon Coburn in London as well as Alfred Stieglitz and Gertrude Käsebier in New York. Prior to opening her own portrait studio, she worked at the Edward S. Curtis studio perfecting her technique.

Later in her career, she collaborated with Edward Weston and others in the Group f/64, and with Ansel Adams in the formation of the photographic program at the California School of Fine Arts.

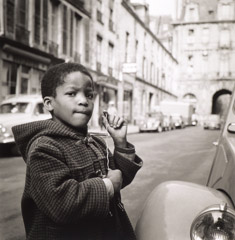

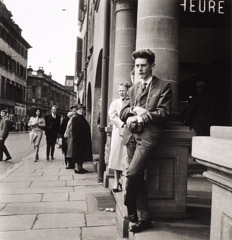

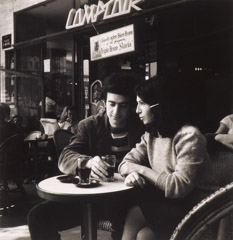

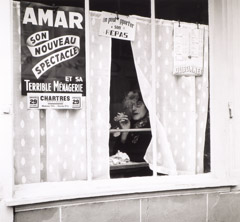

In 1960, Cunningham returned to Europe to photograph and to visit with other artists such as Man Ray. We have chosen the seldom seen images from that series for this exhibition.

More information on Imogen Cunningham can be found on his Artist Page

Below Are Recent Dialogue Posts

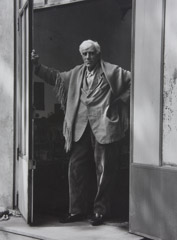

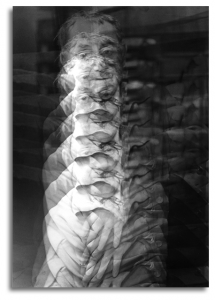

Abbott/Cunningham - Out Man Raying Man Ray

The Art of Photographing Photographers

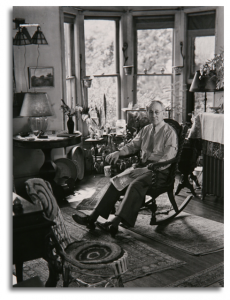

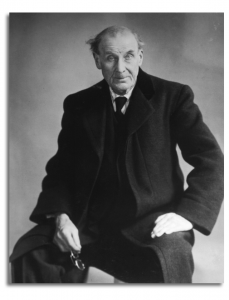

While in Europe, Imogen tracked down the great American expatriate artist Man Ray and made a stunning portrait of this multi-disciplinary artist. Often in her long career, Imogen used darkroom magic to transform an ordinary photograph, into something much more.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

Imogen Cunningham - The Chop

Ideas Without End

When examining Imogen Cunningham Estate prints, one cannot help but notice the Chinese characters that lie to the right of her signature. A chop is an East Asian printing stamp that is used in lieu of a signature made with a pen in some Asian countries. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

These stamps can be made of metal, stone, plastic, ivory and so forth and make an indentation on paper when pressure is applied. Imogen’s chop is very special as it was developed by Imogen and designed by Shen Yao, a friend of Imogen’s and a Professor of Linguistics at the University of Hawaii.

These stamps can be made of metal, stone, plastic, ivory and so forth and make an indentation on paper when pressure is applied. Imogen’s chop is very special as it was developed by Imogen and designed by Shen Yao, a friend of Imogen’s and a Professor of Linguistics at the University of Hawaii.The Persistence of Vision

Creativity and Longevity in the Careers of:

Imogen Cunningham, Bernice Abbott and Paul Strand

Bernice Abbott was part of the American expatriate community in Paris in the 1920s. After studying sculpture in Europe for a few years, she found her calling when she convinced Dadaist Man Ray to hire her as a darkroom assistant, despite her lack of experience.

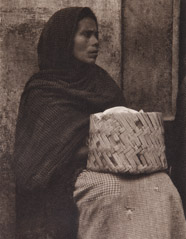

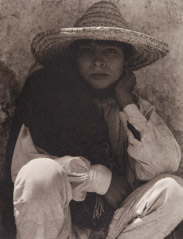

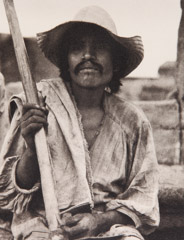

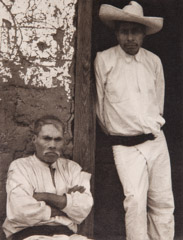

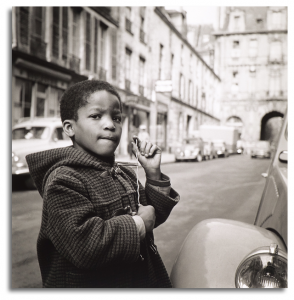

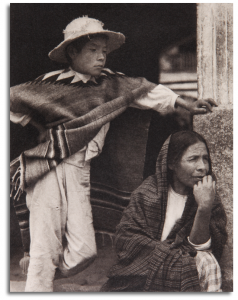

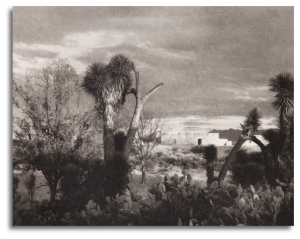

Paul Strand moved to Mexico in the 1930s to photograph labor and farming communities, after being invited by Carlos Chavez, director of the fine arts department of the Secretariat of Public Education, to document the changing landscape and people of Mexico. During the two years Strand spent there, he traveled the countryside photographing small towns, churches, religious icons and the people who inhabited the land. Eventually, Strand moved to France permanently in the 1950s. His adopted country became a base to explore Europe and Africa.

For part of her career, Imogen Cunningham was restricted geographically by familial duties, but she also traveled to Europe at the end of her life and photographed extensively there. Though her photographic endeavors were primarily centered on the West Coast, her projects where as diverse and expansive, as those of her peers in the Circle of Light exhibition.

Imogen In Paris

Though Imogen Cunningham is often associated with West Coast photographers, such as Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, who also came to prominence in the greater San Francisco area in the 1930’s, her photographic origins are equally rooted in the European tradition. As a young woman Imogen traveled to Dresden, Germany to study chemistry and photography in 1909. This was a bold step for a woman at the turn of the Twentieth Century; one of many pioneering courses Imogen would chart in her long life. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

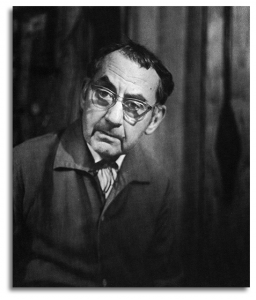

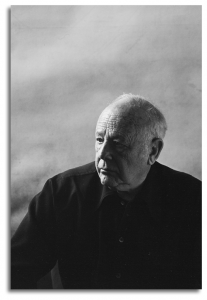

Paul Strand (1890-1976)

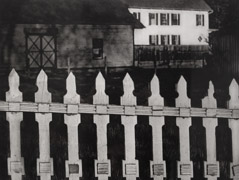

Strand studied photography in New York with Lewis Hine, who was dedicated to social and political reform. Later, with Alfred Stieglitz’ mentorship, and influenced by Stieglitz’ promotion of modern art, he became an early advocate of photographic modernism.

Whether in his portraits, landscapes, still lifes, or studies of architecture, Strand preserved a quality of directness and intimacy with his subjects.

Stieglitz said, “Strand’s work is rooted in the best traditions of photography. His vision is potential. His work is pure. He does not rely on tricks of process.”

Ansel Adams commenting on his prints stated, “Paul Strand made the most beautiful photographic prints-excepting nobody living or dead.”

His time in Mexico produced a remarkable set of images that showed his deep appreciation for people and the human spirit. Strand’s iconic White Fence and other images in the show illustrate his sense for the modernist style as well as his interest in village life with his studies in Egypt, France and Italy.

More information on Paul Strand can be found on his Artist Page

Below Are Recent Dialogue Posts

The Intertwined Careers of Lewis Hine, Paul Strand & Bernice Abbott

Social documentary photographer Lewis Hine’s career intersected with two of the Circle of Light artists, Paul Strand and Berenice Abbott. At the dawn of the Twentieth Century, Hine, who was making iconic Ellis Island photographs, taught an extracurricular course at New York’s Ethical Culture School, and one of his students was a young Paul Strand. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

The Persistence of Vision

Creativity and Longevity in the Careers of:

Imogen Cunningham, Bernice Abbott and Paul Strand

Bernice Abbott was part of the American expatriate community in Paris in the 1920s. After studying sculpture in Europe for a few years, she found her calling when she convinced Dadaist Man Ray to hire her as a darkroom assistant, despite her lack of experience.

Paul Strand moved to Mexico in the 1930s to photograph labor and farming communities, after being invited by Carlos Chavez, director of the fine arts department of the Secretariat of Public Education, to document the changing landscape and people of Mexico. During the two years Strand spent there, he traveled the countryside photographing small towns, churches, religious icons and the people who inhabited the land. Eventually, Strand moved to France permanently in the 1950s. His adopted country became a base to explore Europe and Africa.

For part of her career, Imogen Cunningham was restricted geographically by familial duties, but she also traveled to Europe at the end of her life and photographed extensively there. Though her photographic endeavors were primarily centered on the West Coast, her projects where as diverse and expansive, as those of her peers in the Circle of Light exhibition.

Paul Strand and The Photo League

“The Photo League was a remarkable and unique organization, at that time or at any other time. It had no equivalent. They (the members of the Photo League) felt as I have, that the function of art was to speak to people about the world in which they exist.” — Paul StrandREAD ENTIRE ARTICLE

specific pages on the Lumière site.

Paul Strand - Mexican Landscape

Near Saltillo, Mexico, 1932

Paul Strand was immediately smitten with the Mexican landscape upon seeing the terrain from behind the wheel of his Model A Ford in the early days of his sojourn there, according to scholar Calvin Tomkins. In contrast with his earlier mode of photographing landscapes, Strand made some of his best pictures here at first sight.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

Mexico - Paul Strand

When Paul Strand first went to Mexico in 1932, at the invitation of Mexican composer Carlos Chávez, he had no clear intentions to photograph. The Great Depression was underway, and Strand was facing a failing marriage and the dissolution of his relationship with his mentor, Alfred Stieglitz. Mexico, which had just emerged from revolution beckoned many artists of Strand’s generation, whose politics leaned left, towards Communism and Marxism. Mexico was not yet industrialized, and seemed full of promise.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

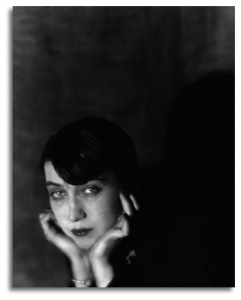

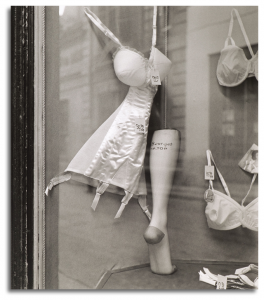

Berenice Abbott (1898-1991)

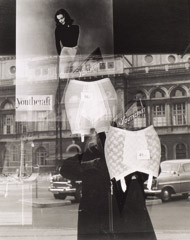

As with Cunningham, Berenice Abbott went to Berlin and Paris to study. Her involvement with photography began in 1923 when Man Ray offered her a position as a studio darkroom assistant. “I took to photography like a duck to water”, she said.

In Paris, Berenice’s portraits were from the literary and artistic community-often shown with those of Man Ray and André Kertész. Her introduction to Eugène Atget by Man Ray led to her acquisition of a great deal of his archive in 1928.

She promoted his work actively, which lead to much of the subsequent recognition of his carefully recorded history of the early architecture of Paris.

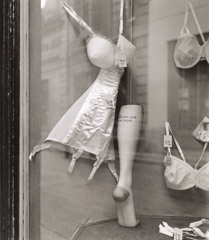

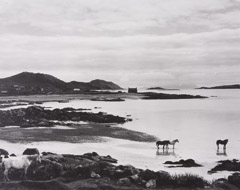

On returning to New York, she photographed New York with much of the rigor that she had learned from Atget. This body of work provides her own archive of historically important New York neighborhoods and architecture in the 1930’s. This led to her Changing New York series.

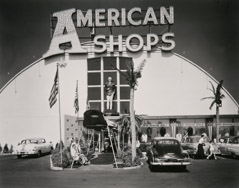

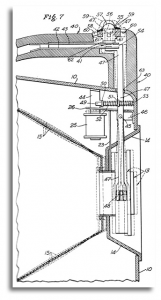

Abbott’s creativity resulted in a number of inventions to facilitate photography. Her interest in science led to a project with MIT using photography to create images for teaching physics. In the 1950’s, she also traveled the length of US Route 1 from Florida to Maine photographing small towns and automobile related architecture.

Berenice Abbott moved from New York to Maine, where she lived until her death in 1991. Her last book was A Portrait of Maine.

More information on Berenice Abbott can be found on her Artist Page

Below Are Recent Dialogue Posts

Berenice Abbott - Inventor

House of Photography

In addition to her artistic accomplishments, Berenice Abbott invented photographic equipment and held four patents on her inventions. In 1947, she and several business associates established The House of Photography, which was a commercial venture designed to bring her inventions to market.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

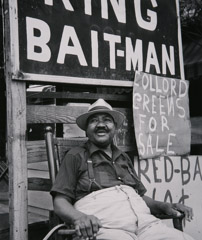

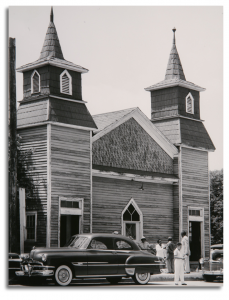

Berenice Abbott - 1411 9th Street, Augusta GA, 1954

Story Behind the Picture

Berenice Abbott’s 1411 9th Street, Augusta, Georgia, 1954

One of the major topics Berenice Abbott addressed in her Route 1 series was racial tension in the south, primarily in Georgia and Florida. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

Before It Disappears - Berenice Abbott

There is a tradition in photography of photographers and photo enthusiasts devoting significant portions of their own careers preserving the work of their artistic heroes whose work was on the verge of extinction. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

Route 1: Berenice Abbott's Unusual Bargain

Imagine this: Berenice Abbott, her trusty view camera, a portable darkroom, a giant schnauzer named Schoen, and a pair of newlyweds, cram into a station wagon and head down Route 1 in the summer of 1954 to photograph small towns along the coast for months on end. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

Abbott/Cunningham - Out Man Raying Man Ray

The Art of Photographing Photographers

While in Europe, Imogen tracked down the great American expatriate artist Man Ray and made a stunning portrait of this multi-disciplinary artist. Often in her long career, Imogen used darkroom magic to transform an ordinary photograph, into something much more.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

The Intertwined Careers of Lewis Hine, Paul Strand & Bernice Abbott

Social documentary photographer Lewis Hine’s career intersected with two of the Circle of Light artists, Paul Strand and Berenice Abbott. At the dawn of the Twentieth Century, Hine, who was making iconic Ellis Island photographs, taught an extracurricular course at New York’s Ethical Culture School, and one of his students was a young Paul Strand. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

The Persistence of Vision

Creativity and Longevity in the Careers of:

Imogen Cunningham, Bernice Abbott and Paul Strand

Bernice Abbott was part of the American expatriate community in Paris in the 1920s. After studying sculpture in Europe for a few years, she found her calling when she convinced Dadaist Man Ray to hire her as a darkroom assistant, despite her lack of experience.

Paul Strand moved to Mexico in the 1930s to photograph labor and farming communities, after being invited by Carlos Chavez, director of the fine arts department of the Secretariat of Public Education, to document the changing landscape and people of Mexico. During the two years Strand spent there, he traveled the countryside photographing small towns, churches, religious icons and the people who inhabited the land. Eventually, Strand moved to France permanently in the 1950s. His adopted country became a base to explore Europe and Africa.

For part of her career, Imogen Cunningham was restricted geographically by familial duties, but she also traveled to Europe at the end of her life and photographed extensively there. Though her photographic endeavors were primarily centered on the West Coast, her projects where as diverse and expansive, as those of her peers in the Circle of Light exhibition.