Berenice Abbott

Berenice Abbott (1898-1991)

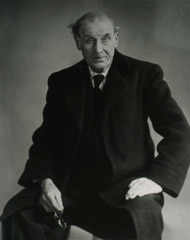

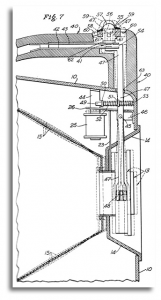

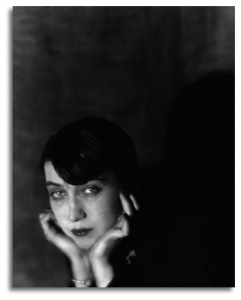

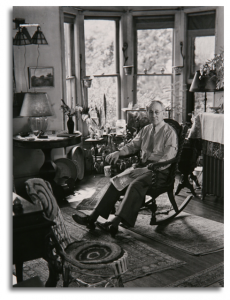

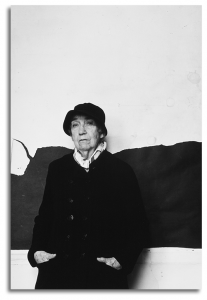

American photographer Berenice Abbott was born in Springfield Ohio in 1898 and died in retirement in Monson, Maine in 1991. Except for a formative and influential decade in Paris in the 1920s, she spent most of her productive life in photography in New York City. Her five decades of accomplishments behind the camera range from portraiture and modernist experimentation to documentation and scientific interpretation. Her contributions as photographic educator, inventor, author and historian are equally diverse: she originated the photography program at the New School for Social Research and taught there from 1934-58; wrote several books and numerous articles including the once influential Guide to Better Photography (1941); received four U.S. patents for photographic and other devices; and rescued the work of French master photographer Eugene Atget.

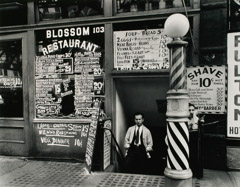

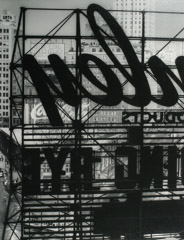

Abbott’s photographs consistently reflect her innate appreciation for the profound documentary capacity of rigorously conceived images to impart information in an aesthetically engaging way. Within four major thematic categories — Portraits (1920s-1930s), New York City (1930s-1940s), Science (1940-1950s), and American Scenes (1930s-1960s) — Abbott’s photographs effectively unite the personal and the impersonal in one penetrating body of work. Her systematic documentary photography of New York City for the Federal Arts Project during 1935-1939, Changing New York is the subject pictured here.

copyright Julia Van Haaften

Born: July 17, 1898 Springfield, Ohio

Died: December 9, 1991 Monson, Maine

![]()

The work of Berenice Abbott is featured in these exhibitions.

(Select the image to view the exhibition page)

The work of Berenice Abbott is featured in these Theme Collections.

(Select the image to view the theme page)

Numerous books have been published on the photography of Berenice Abbott, featured below are 2 more recent editions.

Berenice Abbott (2 Volume Set)

Published 2008

Publisher: Steidl

ISBN 978-3-86521-592-5

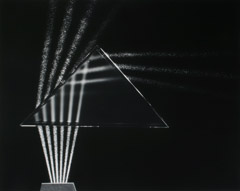

Berenice Abbott Documenting Science

Published 2012

Publisher: Steidl

ISBN 978-3-86930-431-1

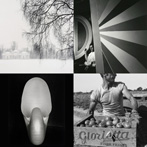

Berenice Abbott - Inventor

House of Photography

In addition to her artistic accomplishments, Berenice Abbott invented photographic equipment and held four patents on her inventions. In 1947, she and several business associates established The House of Photography, which was a commercial venture designed to bring her inventions to market.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

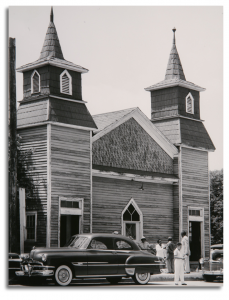

Berenice Abbott - 1411 9th Street, Augusta GA, 1954

Story Behind the Picture

Berenice Abbott’s 1411 9th Street, Augusta, Georgia, 1954

One of the major topics Berenice Abbott addressed in her Route 1 series was racial tension in the south, primarily in Georgia and Florida. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

Before It Disappears - Berenice Abbott

There is a tradition in photography of photographers and photo enthusiasts devoting significant portions of their own careers preserving the work of their artistic heroes whose work was on the verge of extinction. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

Route 1: Berenice Abbott's Unusual Bargain

Imagine this: Berenice Abbott, her trusty view camera, a portable darkroom, a giant schnauzer named Schoen, and a pair of newlyweds, cram into a station wagon and head down Route 1 in the summer of 1954 to photograph small towns along the coast for months on end. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

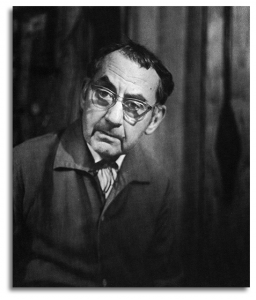

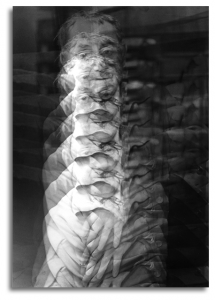

Abbott/Cunningham - Out Man Raying Man Ray

The Art of Photographing Photographers

While in Europe, Imogen tracked down the great American expatriate artist Man Ray and made a stunning portrait of this multi-disciplinary artist. Often in her long career, Imogen used darkroom magic to transform an ordinary photograph, into something much more.READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

The Intertwined Careers of Lewis Hine, Paul Strand & Bernice Abbott

Social documentary photographer Lewis Hine’s career intersected with two of the Circle of Light artists, Paul Strand and Berenice Abbott. At the dawn of the Twentieth Century, Hine, who was making iconic Ellis Island photographs, taught an extracurricular course at New York’s Ethical Culture School, and one of his students was a young Paul Strand. READ ENTIRE ARTICLE

The Persistence of Vision

Creativity and Longevity in the Careers of:

Imogen Cunningham, Bernice Abbott and Paul Strand

Bernice Abbott was part of the American expatriate community in Paris in the 1920s. After studying sculpture in Europe for a few years, she found her calling when she convinced Dadaist Man Ray to hire her as a darkroom assistant, despite her lack of experience.

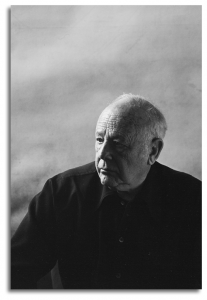

Paul Strand moved to Mexico in the 1930s to photograph labor and farming communities, after being invited by Carlos Chavez, director of the fine arts department of the Secretariat of Public Education, to document the changing landscape and people of Mexico. During the two years Strand spent there, he traveled the countryside photographing small towns, churches, religious icons and the people who inhabited the land. Eventually, Strand moved to France permanently in the 1950s. His adopted country became a base to explore Europe and Africa.

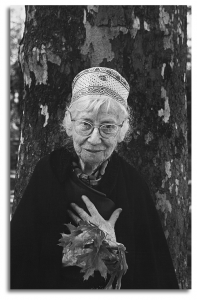

For part of her career, Imogen Cunningham was restricted geographically by familial duties, but she also traveled to Europe at the end of her life and photographed extensively there. Though her photographic endeavors were primarily centered on the West Coast, her projects where as diverse and expansive, as those of her peers in the Circle of Light exhibition.